Introduction

This guide is meant to orient you to the conversation around land acknowledgments in universities and other cultural institutions, and provide resources to help you better understand the history and impact of this practice.

Ultimately, a land acknowledgment is not only a recognition, it is also a commitment (and an ongoing one). These statements, whether written or uttered, remind us that our relationship with the land (which preexists the act of acknowledgment, even if that relationship is tense, estranged, or otherwise challenged and challenging) is vital, and thus encourage us to center our responsibility to place and the other-than-human world. The resources we have curated here will help you better understand how to engage in a thoughtful practice of acknowledgement and recognition, of the land and the communities who have continuously cared for our world across time, while also challenging you to engage more deeply with Indigenous experiences and decolonial perspectives.

"Land is more than the diaphanousness of inhabited memories; Land is spiritual, emotional, and relational; Land is experiential, (re)membered, and storied; Land is consciousness—Land is sentient. Land refers to the ways we honor and respect her as a sentient and conscious being. Therefore, in acknowledgment of the fundamental being of Land I always capitalize Land. I have come to know Land both as a fundamental sentient being and as a philosophical construct."

—Sandra Styres (Kanien'kehá:ka) from "Literacies of Land: Decolonizing Narratives, Storying, and Literature" (in Indigenous and Decolonizing Studies in Education)

Living Land Acknowledgment

We are always on Indigenous land.

We are always on Indigenous land.

Indiana University and the city of Bloomington occupy lands of enduring historical and cultural significance, and that for some was, is, and will always be home, to a number of Indigenous groups, including the myaamiaki (Miami), Lënape (Delaware), saawanwa (Shawnee), kiikaapoa (Kickapoo), and Neshnabé/Bodwéwadmik (Potawatomi) peoples. We honor and acknowledge the ancestral and contemporary caretakers of this place, as well as our nonhuman spirits, elders, and guides, offer gratitude for being held and nourished by the land, and recognize the inherent sovereignty and resilience of all Native communities who have survived and still thrive to this day on Turtle Island in spite of the systemic subjugation, dispossession, and genocide that constitute the ongoing reality of settler-colonialism.

As learners, educators, and librarians, we will actively endeavor to challenge the legacies of settler-colonialism and Indigenous oppression, reject extractive and exploitative logics (both material and conceptual), continue to enact an orientation of humility, gratitude, and reciprocity toward/with local and trans-national Indigenous communities, and work to honor those who are here with us today.

We encourage all, settlers and guests alike, to look beyond acknowledgement and engage with local Indigenous communities while also cultivating thoughtful relations of reciprocity with the sacred land you live on, as well as the many vibrant beings with whom you share it.

Image: "Indigenize Indiana" logo from the First Nations Educational and Cultural Center.

An Invitation toward Movement and Reflection

As you are learning more about the land and Indigenous communities, and perhaps in the process of crafting your own territorial/land acknowledgments, here are some ideas for reorienting towards place and these communities, wherever you are in time and space:

- Know where you are - If you are a settler on Turtle Island, or another place that was occupied by colonizers, do you know whose land are you on? Do you know what communities used to live and thrive on this land? You can use tools like Native Land to find out; remember that a land acknowledgment is both about acknowledging Indigenous people and cultivating a relationship with land and place

- Learn the history of this place - As you come into more knowledge, take a moment to reflect with humility on what you've been taught about the land you live on and the history of that place and the people who once lived there, and perhaps still do. You can use some of the resources below, as well as primary source databases, to learn more

- Engage with Indigenous stories and communities - Once you've engaged in this reflective practice, which is an ongoing process without a necessary end point, do some research about the people and communities who were (or are) indigenous to that place. Find out where they are now (where they were displaced to), and get to know their stories, histories, and experiences. You might find books, articles, or other media (such as music and films) by creators and artists from these communities, learn about their cultural events and traditions, and slowly develop a relationship with them in the present

- Listen and act - Along the way, and as these connections deepen, listen and pay attention to what your Native neighbors, colleagues, and friends are asking of you, their settler neighbors and the descendants of colonizers. Open yourself to supporting them through actions, solidarity work, organizing, and consciousness raising. What do they need from you? What political requests do Indigenous people have that haven't been met? Were there treaties or other agreements made to them that weren’t upheld? How can you commit to and renew those commitments with yourself and in your communities?

- Stay in the process and remain open - Offer support when and how you can, based on and being led by Indigenous people, organizations, and communities. Continue learning and unlearning. Stay open and keep caring. And when you're ready, go deeper: there is much we can learn from our nonhuman (animal, plant, fungal, and beyond) companions as well

For more support with this work and process, please see some of the resources we've collected below.

Acknowledgment Resources

"Land is a gift, a relative, a body that sustains other bodies. And if the land is our relative, then we cannot simply acknowledge it as land. We must understand what our responsibilities are to the land as our kin. We must engage in a reciprocal relationship with the land. Land is—in its animate multiplicities—an ongoing enactment of reciprocity."

—Joseph M. Pierce (ᏣᎳᎩᎯ ᎠᏰᎵ / Cherokee) from "Your Land Acknowledgment is Not Enough"

If you'd to learn more about the practice and history of indigenous land acknowledgments, consult the various resources listed in this guide. Here are a few entry points:

- Native Land Interactive Map

- First Nations Educational & Cultural Center @ IU (FNECC)

- What are land acknowledgements and why do they matter? (Local Love)

- Indigenous Land Acknowledgment, Explained (Teen Vogue)

On the history of Indigenous communities in the state of Indiana:

- The Naming of Indiana (Indiana Historical Bureau)

- Indigenous Tribes of Indiana (American Library Association)

- Indian Removals in Indiana (Wikipedia)

- The Rust Belt is Indigenous Land (Belt Magazine)

Treaties in Indiana

- Treaty of Greenville (1795)

- Treaty of Vincennes (1803)

- Treaty of Grouseland (1805)

- Treaty of Fort Wayne (1809)

- Treaty of St. Mary's (1818)

- Treaty of Chicago (1821)

- Treaty of Mississinewas (1826)

- Treaty of Tippecanoe (1832)

- Treaty of the Wabash (1840)

Once you're ready to begin crafting a land or territorial acknowledgment, these resources can help guide you:

- Land Acknowledgment & Resources (FNECC @ IU)

- Guide to Indigenous Land Acknowledgments (Native Governance Center)

- Territory Acknowledgement Resource Page (Native Land)

- Land Acknowledgment Toolkit (CSUSM)

- Guide to Indigenous Land and Territorial Acknowledgments for Cultural Institutions (NYU)

- Version with further resources on the updated website

Articles & Essays

- Beyond Territorial Acknowledgments (Apihtawikosisan)

- Burial Ground Acknowledgments (The New Inquiry)

- Beyond the Land Acknowledgment (Hack the Gates)

- 'Land Acknowledgments' Are Just Moral Exhibitionism (The Atlantic)

- "Land acknowledgments meant to honor Indigenous people too often do the opposite – erasing American Indians and sanitizing history instead" (The Conversation)

- "Your Land Acknowledgment is Not Enough" (Hyperallergic)

Interviews

- Indigenous Artists' Perspectives on Land Acknowledgments (Vice)

- 'I regret it': Hayden King on writing Ryerson University's territorial acknowledgement (CBC Radio)

- Interview with Endawnis Spears on Land Acknowledgment & Native Communities (Federation of State Humanities Councils)

Panels/Discussions

- Land Acknowledgment Panel (IU Bloomington Faculty Council (BFC) Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) Committee)

- We Are All on Native Land: A Conversation about Land Acknowledgments (The Field Museum)

- Indigenous Land Acknowledgment (Native Governance Center)

Scholarly Articles

Ambo, T. S., & Yang, K. W. (2021). Beyond Land Acknowledgment in Settler Institutions. Social Text, 39(1), 21–46. https://doi-org.proxyiub.uits.iu.edu/10.1215/01642472-8750076

Bell, C. (2020). Unsettling Existence: Land acknowledgement in contemporary Indigenous performance. Performance Research, 25(2), 141–148. https://doi-org.proxyiub.uits.iu.edu/10.1080/13528165.2020.1752587

Blenkinsop, S., & Fettes, M. (2020). Land, Language and Listening: The Transformations That Can Flow from Acknowledging Indigenous Land. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 54(4), 1033–1046.

Daigle, M. (2019). The spectacle of reconciliation: On (the) unsettling responsibilities to Indigenous peoples in the academy. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 37(4), 703–721. https://doi-org.proxyiub.uits.iu.edu/10.1177/0263775818824342

Huntington, H. P. (2021). What Do Land Acknowledgments Acknowledge? Environment, 63(4), 31–35. https://doi-org.proxyiub.uits.iu.edu/10.1080/00139157.2021.1924579

Rethinking the Practice and Performance of Indigenous Land Acknowledgement. (2019). Canadian Theatre Review, 177, 20–30. https://doi-org.proxyiub.uits.iu.edu/10.3138/ctr.177.004

To learn more about the tribes, nations, and communities with ties to this land colonially known as the state of Indiana, check out their websites and consider supporting them in an ongoing way however you can:

Myaamiaki (Miami)

Lënape (Delaware)

- Delaware Nation (OK)

- Delaware Tribe of Indians (OK)

Saawanwa (Shawnee)

- Absentee Shawnee Tribe (OK)

- Eastern Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma (OK)

- Shawnee Tribe (OK)

Kiikaapoa (Kickapoo)

Neshnabé/Bodwéwadmik (Potawatomi)

- Citizen Potawatomi Nation (OK)

- Forest County Potawatomi (WI)

- Gun Lake Tribe (MI)

- Hannahville Indian Community (MI)

- Nottawaseppi Huron Band of Potawatomi (MI)

- Pokagon Band of Potawatomi (IN & MI)

- Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation (KS)

Indigenous-led organizations and movements to learn about and listen to:

- Decolonize This Place

- The Red Nation

- NDN Collective

- Seeding Sovereignty

- Indian Land Tenure Foundation (ILTF)

- Sogorea Te’ Land Trust

- Honor the Earth

- Native American Food Sovereignty Alliance

- Native Justice Coalition

- Lakota People's Law Project

Suggestions for Indigenous organizations and projects to support and engage with:

- Suggestions for Native Organizations to Support (Language Magazine)

- 10 Native Activism Organizations to Support (Teen Vogue)

- Queer Projects on Indigenous Land (The Sogorea Te Land Trust)

Native organizations and other relevant institutions in Indiana:

Going deeper, towards a decolonial future

Read

- Decolonize Your Bookshelf (Electric Literature)

- Decolonize Your Bookshelf (Verso)

- 22 Books By Indigenous Writers to Read Right Now (Chicago Review of Books)

- The James Welch Native Lit Festival

Learn

- Native Knowledge 360° Education Initiative (Smithsonian)

- 100 Years of Land Struggle (Briarpatch)

- Land Grab Universities (High Country News)

- Does Your Local Museum or University Still Have Native American Remains? (ProPublica)

- Note: IU has the 5th largest collection of unrepatriated Native American remains in the U.S.

Act

- Land Reparations & Indigenous Solidarity Toolkit (Resource Generation)

- Resource Guide to Reparations and Land Rematriation on Turtle Island (Google Doc)

- Beyond Land Acknowledgment Guide (Native Governance Center)

- Indigenizing the Academy (University Affairs)

- Landback Campaign (NDN Collective)

- #LandBack is Climate Justice (Lakota People's Law Project)

- Rematriate the Land Fund (Sogorea Te’ Land Trust)

- How to Be an Ally to Indigenous Peoples: A White Paper in the Spirit of a Red Paper (Seventh Generation Fund)

- Going Beyond Land Acknowledgements Resource Library (Redbud Resource Group)

Recommended Local Indigenous Resources

The resources gathered here are meant to continue pushing members of the Indiana University community beyond land acknowledgments, and to approach this work with humility and engage with the experiences and perspectives of Indigenous people, particularly the myaamiaki (Miami), Lënape (Delaware), saawanwa (Shawnee), Neshnabé/Bodwéwadmik (Potawatomi), and kiikaapoa (Kickapoo) peoples, in their own voices. Our goal is to amplify the stories, poetry, artwork, film, and resources created by members of these communities to helps all of us, especially settlers and guests on this land, to become more self-aware and accountable.

We've also included a selection of foundational works of Indigenous history and culture, as well as a brief overview of recommended works by non-Native creators about these groups with roots in this place.

About the Playlist

This mix features artists from the tribes and communities recognized by IU as past, present, and future caretakers of the land this institution occupies. A work in progress, we welcome suggestions for artists from these groups for inclusion.

Note: To enjoy the playlist in full, click on the white Spotify icon in the upper-right corner of the playlist, and press the "like" (♡) button in the application to save.

Foundational resources by Native creators and artists relevant to Indigenous history, culture, and experience, from outside of the five nations, tribes, and groups we recognize and acknowledge as connected to this land. If you are just getting started on learning about Indigeneity, this is a good place to begin exploring

-

Shapes of Native Nonfiction: collected essays by contemporary writers by

ISBN: 9780295745763Publication Date: 2019-06-01Just as a basket's purpose determines its materials, weave, and shape, so too is the purpose of the essay related to its material, weave, and shape. Editors Elissa Washuta and Theresa Warburton ground this anthology of essays by Native writers in the formal art of basket weaving. Using weaving techniques such as coiling and plaiting as organizing themes, the editors have curated an exciting collection of imaginative, world-making lyric essays by twenty-seven contemporary Native writers from tribal nations across Turtle Island into a well-crafted basket. Shapes of Native Nonfiction features a dynamic combination of established and emerging Native writers, including Stephen Graham Jones, Deborah Miranda, Terese Marie Mailhot, Billy-Ray Belcourt, Eden Robinson, and Kim TallBear. Their ambitious, creative, and visionary work with genre and form demonstrate the slippery, shape-changing possibilities of Native stories. Considered together, they offer responses to broader questions of materiality, orality, spatiality, and temporality that continue to animate the study and practice of distinct Native literary traditions in North America. -

As We Have Always Done: indigenous freedom through radical resistance by

ISBN: 9781517903862Publication Date: 2017-10-17Across North America, Indigenous acts of resistance have in recent years opposed the removal of federal protections for forests and waterways in Indigenous lands, halted the expansion of tar sands extraction and the pipeline construction at Standing Rock, and demanded justice for murdered and missing Indigenous women. In As We Have Always Done, Leanne Betasamosake Simpson locates Indigenous political resurgence as a practice rooted in uniquely Indigenous theorizing, writing, organizing, and thinking. Indigenous resistance is a radical rejection of contemporary colonialism focused around the refusal of the dispossession of both Indigenous bodies and land. Simpson makes clear that its goal can no longer be cultural resurgence as a mechanism for inclusion in a multicultural mosaic. Instead, she calls for unapologetic, place-based Indigenous alternatives to the destructive logics of the settler colonial state, including heteropatriarchy, white supremacy, and capitalist exploitation. -

The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee: Native America from 1890 to the present by

ISBN: 9781594633157Publication Date: 2019-01-22Beginning with the tribes' devastating loss of land and the forced assimilation of their children at government-run boarding schools, he shows how the period of greatest adversity also helped to incubate a unifying Native identity. He traces how conscription in the US military and the pull of urban life brought Indians into the mainstream and modern times, even as it steered the emerging shape of their self-rule and spawned a new generation of resistance. The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee is an essential, intimate history - and counter-narrative - of a resilient people in a transformative era. -

Braiding Sweetgrass: indigenous wisdom, scientific knowledge and the teachings of plants by

ISBN: 9781571313355Publication Date: 2013-10-15An inspired weaving of indigenous knowledge, plant science, and personal narrative from a distinguished professor of science and a Native American whose previous book, Gathering Moss, was awarded the John Burroughs Medal for outstanding nature writing. As a botanist and professor of plant ecology, Robin Wall Kimmerer has spent a career learning how to ask questions of nature using the tools of science. As a Potawatomi woman, she learned from elders, family, and history that the Potawatomi, as well as a majority of other cultures indigenous to this land, consider plants and animals to be our oldest teachers. In Braiding Sweetgrass, Kimmerer brings these two lenses of knowing together to reveal what it means to see humans as "the younger brothers of creation." As she explores these themes she circles toward a central argument: the awakening of a wider ecological consciousness requires the acknowledgement and celebration of our reciprocal relationship with the world. Once we begin to listen for the languages of other beings, we can begin to understand the innumerable life-giving gifts the world provides us and learn to offer our thanks, our care, and our own gifts in return. -

Everything You Wanted to Know about Indians but Were Afraid to Ask by

ISBN: 9780873518611Publication Date: 2012-05-01"I had a profoundly well-educated Princetonian ask me, 'Where is your tomahawk?' I had a beautiful woman approach me in the college gymnasium and exclaim, 'You have the most beautiful red skin.' I took a friend to see Dances with Wolves and was told, 'Your people have a beautiful culture.' I made many lifelong friends at college, and they supported but also challenged me with questions like, 'Why should Indians have reservations?'" What have you always wanted to know about Indians? Do you think you should already know the answers—or suspect that your questions may be offensive? In matter-of-fact responses to over 120 questions, both thoughtful and outrageous, modern and historical, Ojibwe scholar and cultural preservationist Anton Treuer gives a frank, funny, and sometimes personal tour of what's up with Indians, anyway. What is the real story of Thanksgiving? Why are tribal languages important? What do you think of that incident where people died in a sweat lodge? Everything You Wanted to Know about Indians but Were Afraid to Ask cuts through the emotion and builds a foundation for true understanding and positive action. -

Algonquian Spirit: contemporary translations of the Algonquian literatures of North America by

ISBN: 9780803293380Publication Date: 2005-12-01When Europeans first arrived on this continent, Algonquian languages were spoken from the northeastern seaboard through the Great Lakes region, across much of Canada, and even in scattered communities of the American West. The rich and varied oral tradition of this Native language family, one of the farthest-flung in North America, comes brilliantly to life in this remarkably broad sampling of Algonquian songs and stories from across the centuries. Ranging from the speech of an early unknown Algonquian to the famous Walam Olum hoax, from retranslations of "classic" stories to texts appearing here for the first time, these are tales written or told by Native storytellers, today as in the past, as well as oratory, oral history, and songs sung to this day. An essential introduction and captivating guide to Native literary traditions still thriving in many parts of North America, Algonquian Spirit contains vital background information and new translations of songs and stories reaching back to the seventeenth century. Drawing from Arapaho, Blackfeet, Cheyenne, Cree, Delaware, Maliseet, Menominee, Meskwaki, Miami-Illinois, Mi'kmaq, Naskapi, Ojibwe, Passamaquoddy, Potawatomi, and Shawnee, the collection gathers a host of respected and talented singers, storytellers, historians, anthropologists, linguists, and tribal educators, both Native and non-Native, from the United States and Canada--all working together to orchestrate a single, complex performance of the Algonquian languages. -

When the Light of the World Was Subdued, Our Songs Came Through by

ISBN: 9780393356809Publication Date: 2020-08-25This landmark anthology celebrates the indigenous peoples of North America, the first poets of this country, whose literary traditions stretch back centuries. Opening with a blessing from Pulitzer Prize-winner N. Scott Momaday, the book contains powerful introductions from contributing editors who represent the five geographically organized sections. Each section begins with a poem from traditional oral literatures and closes with emerging poets, ranging from Eleazar, a seventeenth-century Native student at Harvard, to Jake Skeets, a young Diné poet born in 1991, and including renowned writers such as Luci Tapahanso, Natalie Diaz, Layli Long Soldier, and Ray Young Bear. When the Light of the World Was Subdued, Our Songs Came Through offers the extraordinary sweep of Native literature, without which no study of American poetry is complete.

Tribal Resources

The Miami Nation of Indiana (also known as the Miami Nation of Indians of the State of Indiana) is headquartered in Peru, Indiana. The Indiana Miami, or Eastern Miami, signed a treaty with the United States on June 5, 1854; however, its federal recognition was terminated in 1897. The United States Congress has consistently refused to authorize federal recognition of the Indiana Miami as a tribal group separate from the Western Miami, the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma.

- Miami Nation of Indians of the State of Indiana Website

- aacimotaatiiyankwi.org (A Myaamia Community Blog)

- Selected blog posts:

- A Myaamia Beginning A Story of Emergence

- Removal Commemoration

- Selected blog posts:

- The Myaamia Center's YouTube channel (Miami University's Myaamia Center)

- Suggested Videos:

- Mahkihkiwa: Myaamia Ethnobotanical Database

Books

-

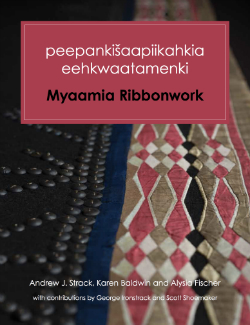

Peepankisaapiikahkia Eehkwaatamenki: Myaamia Ribbonwork

by

ISBN: 9780976583790Publication Date: 2015-07-01When a culture reawakens, that renewal can come in many forms. This book is part of the Myaamia community's ongoing cultural revitalization and aims to educate about the rich history of Miami patterns and their application to ribbonwork beginning in the late 1700s. Myaamia people used the geometric ribbonwork to adorn clothing for special occasions for both men and women, especially leggings, skirts and moccasins. This text is designed to assist in the reawakening of ribbonwork among the Miamis and includes: A history of Miami ribbonwork showing how the geometric patterns were used with other materials as well, instructions for 3 ribbonwork projects, along with a list of necessary supplies and illustrated explanations of the various stitches used, images of historic Miami ribbonwork found in North American collections, and examples of contemporary uses for ribbonwork patterns to help inspire community members to find ways to bring ribbonwork patterns into their daily lives.

Peepankisaapiikahkia Eehkwaatamenki: Myaamia Ribbonwork

by

ISBN: 9780976583790Publication Date: 2015-07-01When a culture reawakens, that renewal can come in many forms. This book is part of the Myaamia community's ongoing cultural revitalization and aims to educate about the rich history of Miami patterns and their application to ribbonwork beginning in the late 1700s. Myaamia people used the geometric ribbonwork to adorn clothing for special occasions for both men and women, especially leggings, skirts and moccasins. This text is designed to assist in the reawakening of ribbonwork among the Miamis and includes: A history of Miami ribbonwork showing how the geometric patterns were used with other materials as well, instructions for 3 ribbonwork projects, along with a list of necessary supplies and illustrated explanations of the various stitches used, images of historic Miami ribbonwork found in North American collections, and examples of contemporary uses for ribbonwork patterns to help inspire community members to find ways to bring ribbonwork patterns into their daily lives. -

Myaamia Neehi Peewaalia Kaloosioni Mahsinaakani: A Miami-Peoria Dictionary

by

ISBN: 9780976583707Publication Date: 2005-01-01This dictionary consists of words, phrases and sentences collected from a variety of original documents spanning 300 years. The earliest resources on the Miami-Peoria language are the works of Jesuit missionaries from the late seventeenth century. The most recent works are from the last generation of Miami-Peoria speakers in the early to mid twentieth century. Of the known records, this dictionary only represents a fraction of what has been uncovered. It will be years, maybe even a couple of generations, before we are able to document all of the forms found in these historical manuscripts.

Myaamia Neehi Peewaalia Kaloosioni Mahsinaakani: A Miami-Peoria Dictionary

by

ISBN: 9780976583707Publication Date: 2005-01-01This dictionary consists of words, phrases and sentences collected from a variety of original documents spanning 300 years. The earliest resources on the Miami-Peoria language are the works of Jesuit missionaries from the late seventeenth century. The most recent works are from the last generation of Miami-Peoria speakers in the early to mid twentieth century. Of the known records, this dictionary only represents a fraction of what has been uncovered. It will be years, maybe even a couple of generations, before we are able to document all of the forms found in these historical manuscripts. -

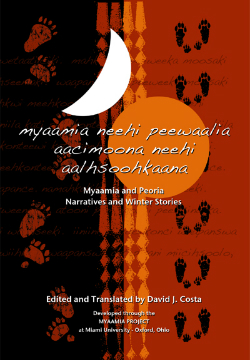

Myaamia Neehi Peewaalia Aacimoona Neehi Aalhsoohkaana: Myaamia and Peoria Narratives and Winter Stories

by

ISBN: 9780976583769Publication Date: 2010-09-01Myaamia and Peoria are two dialects of an Algonquian language originally spoken in the upper Midwest, primarily in what is now Indiana and Illinois. This language was originally spoken by several tribes, the main ones being the Myaamia, Peoria, Wea, Kashaskia, and Piankashaw. This book is the first collection of native texts from the Myaamia and Peoria ever published. Of the forty-five texts it contains, sixteen are in English only, and twenty-nine are in the Myaamia, Peoria or Wea dialects, with English translations. These texts were collected from several different people from the mid-1890's through 1916, and include origin and cultural hero stories, trickster stories, (including several stories of Fox and Wolf), animal stories, biographical, autobiographical and historical narratives, how-to stories, and Christian prayers. These stories will be of great interest to present-day members of the Myaamia and Peoria tribes, not only for the priceless information they provide towards an understanding of the Myaamia-Peoria language, but also for their invaluable insights into the lives, cultures and beliefs of the members of the Myaamia and Peoria tribes, information delivered in their own words, not recast in the perceptions of outsiders.

Myaamia Neehi Peewaalia Aacimoona Neehi Aalhsoohkaana: Myaamia and Peoria Narratives and Winter Stories

by

ISBN: 9780976583769Publication Date: 2010-09-01Myaamia and Peoria are two dialects of an Algonquian language originally spoken in the upper Midwest, primarily in what is now Indiana and Illinois. This language was originally spoken by several tribes, the main ones being the Myaamia, Peoria, Wea, Kashaskia, and Piankashaw. This book is the first collection of native texts from the Myaamia and Peoria ever published. Of the forty-five texts it contains, sixteen are in English only, and twenty-nine are in the Myaamia, Peoria or Wea dialects, with English translations. These texts were collected from several different people from the mid-1890's through 1916, and include origin and cultural hero stories, trickster stories, (including several stories of Fox and Wolf), animal stories, biographical, autobiographical and historical narratives, how-to stories, and Christian prayers. These stories will be of great interest to present-day members of the Myaamia and Peoria tribes, not only for the priceless information they provide towards an understanding of the Myaamia-Peoria language, but also for their invaluable insights into the lives, cultures and beliefs of the members of the Myaamia and Peoria tribes, information delivered in their own words, not recast in the perceptions of outsiders. -

Asiihkiwi Neehi Kiisikwi Myaamionki: Earth and Sky: The Place of the Myaamiaki by

ISBN: 9780976583776Publication Date: 2011-01-01ašiihkiwi neehi kiišikwi myaamionki: Earth and Sky, The Place of the Myaamiaki is a curriculum that explores the Earth and Sky from a Myaamia perspective. Designed to engage the entire family, the curriculum includes illustrated stories that can be read to our youngest learners, and permits teachers to help students better understand the world through the perspective of their Myaamia culture. -

As Long As the Earth Endures: annotated Miami-Illinois texts by

ISBN: 9781496228567Publication Date: 2022-02-01As Long as the Earth Endures is an annotated collection of almost all of the known Native texts in Miami-Illinois, an Algonquian language of Indiana, Illinois, and Oklahoma. These texts, gathered from native speakers of Myaamia, Peoria, and Wea in the 1890s and the early twentieth century, span several genres, such as culture hero stories, trickster tales, animal stories, personal and historical narratives, how-to stories, and translations of Christian materials. These texts were collected from seven speakers: Frank Beaver, George Finley, Gabriel Godfroy, William Peconga, Thomas Richardville, Elizabeth Valley, and Sarah Wadsworth. Representing thirty years of study, almost all of the stories are published here for the first time. The texts are presented with their original transcriptions along with full, corrected modern transcriptions, translations, and grammatical analyses. Included with the texts are extensive annotation on all aspects of their meaning, pronunciation, and interpretation; a lengthy glossary explaining and analyzing in detail every word; and an introduction placing the texts in their philological, historical, linguistic, and folkloric context, with a discussion of how the stories compare to similar texts from neighboring Great Lakes Algonquian tribes. -

Myaamiaki Isi Meehtohseeniwiciki: How the Miami People Live

by

ISBN: 9780976583752Publication Date: 2010-01-01This project is made possible by a grant from the U.S. Institute of Museum and Library Services. Additional support received from the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma, Miami Tribe of Oklahoma's Cultural Resources Office, and the Myaamia Heritage Museum & Archive.

Myaamiaki Isi Meehtohseeniwiciki: How the Miami People Live

by

ISBN: 9780976583752Publication Date: 2010-01-01This project is made possible by a grant from the U.S. Institute of Museum and Library Services. Additional support received from the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma, Miami Tribe of Oklahoma's Cultural Resources Office, and the Myaamia Heritage Museum & Archive.

This booklet is the first part of a grant provided by the Institute of Museum and Library Services. It is intended to give a review of the exhibition that was housed at the Miami University Art Museum from September 16th to December 13th 2008. You will find pictures of the exhibition installations and close up photos of some specific items throughout the booklet.

Film

-

The Miami Awakening (Miami Language Film)

by

Publication Date: 2009Myaamiaki Eemamwiciki: The Miami Awakening is a Miami language film. Released in May 2009, this film attempts to capture the complexities of reclaiming a language from documentation for the Myaamia people. Dormant-language revitalization is becoming a reality for many tribes and this film challenges the academically imposed label "extinct" that often gets applied to languages that have lost their native speakers. The Myaamia people have experienced unprecedented changes in their community over the last 15 years due to their language and cultural revitalization programs. Although this video was created for the Myaamia community, we hope the story will empower other communities who are trying to revive their languages from documentation.

The Miami Awakening (Miami Language Film)

by

Publication Date: 2009Myaamiaki Eemamwiciki: The Miami Awakening is a Miami language film. Released in May 2009, this film attempts to capture the complexities of reclaiming a language from documentation for the Myaamia people. Dormant-language revitalization is becoming a reality for many tribes and this film challenges the academically imposed label "extinct" that often gets applied to languages that have lost their native speakers. The Myaamia people have experienced unprecedented changes in their community over the last 15 years due to their language and cultural revitalization programs. Although this video was created for the Myaamia community, we hope the story will empower other communities who are trying to revive their languages from documentation.

Visual Arts

-

Megan Sekulich

"Meet Megan Sekulich, a Myaamia student who is currently a Junior at Miami University. Megan is studying Fine Arts with a concentration in print making and also has a minor in Fashion Design. Art has been at the center of our connection to Megan since the first moment that she stepped onto campus–she was recruited into helping with a letterpress print making project before classes even started in her first-year here. Megan has continually connected with the Myaamia Center around how to connect her Myaamia identity to her artwork, and she has even started working at the Myaamia Center as a student worker where she makes imagery for our educational initiatives, such as this blog post where she helped us to visually depict frost." - Kara Strass, Aacimotaatiiyankwi Blog. Megan Sekulich Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/m.sekulich/?hl=en.

Megan Sekulich

"Meet Megan Sekulich, a Myaamia student who is currently a Junior at Miami University. Megan is studying Fine Arts with a concentration in print making and also has a minor in Fashion Design. Art has been at the center of our connection to Megan since the first moment that she stepped onto campus–she was recruited into helping with a letterpress print making project before classes even started in her first-year here. Megan has continually connected with the Myaamia Center around how to connect her Myaamia identity to her artwork, and she has even started working at the Myaamia Center as a student worker where she makes imagery for our educational initiatives, such as this blog post where she helped us to visually depict frost." - Kara Strass, Aacimotaatiiyankwi Blog. Megan Sekulich Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/m.sekulich/?hl=en. -

Julie Olds

Julie (Lankford) Olds was born in Miami, OK, in 1962 and grew up on a small farm in southwest Missouri near the town of Seneca. She showed early promise of the ability to capture a likeness in pencil and studied art through her high school and college years. She studied art at Missouri Southern State University in southwest Missouri and attributes her knowledge and use of several creative materials and mediums to the instruction and encouragement she received from the late Dr. Darrell Dishman.

Julie Olds

Julie (Lankford) Olds was born in Miami, OK, in 1962 and grew up on a small farm in southwest Missouri near the town of Seneca. She showed early promise of the ability to capture a likeness in pencil and studied art through her high school and college years. She studied art at Missouri Southern State University in southwest Missouri and attributes her knowledge and use of several creative materials and mediums to the instruction and encouragement she received from the late Dr. Darrell Dishman.

Julie lives on a farm in rural Miami, OK, with her husband and children. She is a full-time employee by day, serving the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma as Cultural Resources Officer. Her studio is in her home. Natural light illuminates the space where she captures, on paper or canvas, likenesses of community members of all ages engaged in Myaamia living and other subjects relative to her heritage. -

Katrina Mitten

Katrina Mitten is a citizen of the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma, an award winning artist-- beading for over 45 years. Katrina has practiced traditional Great Lakes embroidery style native beadwork through study of family heirlooms, museum collections and practice. The imagery she creates is inspired by the world around her. Her works have been acquired by the Miami Tribe, national museums and private collectors. Illustrating the value she places on education, Katrina has been a corporate lecturer, contributed to elementary, secondary and university level educational programs, and featured in documentary films.

Katrina Mitten

Katrina Mitten is a citizen of the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma, an award winning artist-- beading for over 45 years. Katrina has practiced traditional Great Lakes embroidery style native beadwork through study of family heirlooms, museum collections and practice. The imagery she creates is inspired by the world around her. Her works have been acquired by the Miami Tribe, national museums and private collectors. Illustrating the value she places on education, Katrina has been a corporate lecturer, contributed to elementary, secondary and university level educational programs, and featured in documentary films.

-

Traditional Arts Indiana at IU offers new statewide folk art apprenticeship programKatrina Mitten was a master artist in the 2017 Traditional Arts Indiana’s new statewide apprenticeship program.

Articles

- Leonard, W. (2011). Challenging "Extinction" through Modern Miami Language Practices. American Indian culture and research journal. 35. 135-160. 10.17953/aicr.35.2.f3r173r46m261844.

- Baldwin, D., Costa, D., & Troy, D. (2016). Myaamiaataweenki eekincikoonihkiinki eeyoonki aapisaataweenki: A Miami Language Digital Tool for Language Reclamation. University of Hawaii Press, 10(2016), 394-410.

- Mosley-Howard, G. S., Baldwin, D., Ironstrack, G., Rousmaniere, K., & Burke, B. (2016). Niila Myaamia (I Am Miami): Identity and Retention of Miami Tribe College Students. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 17(4), 437–461.

- Obonyo, V., Troy, D., Baldwin, D., & Clarke, J. (2011). Digital smartpen technology and revitalization of the myaamia language. Journal on Computing and Cultural Heritage, 4(4), 1-11–11.

- Shea, H. (2019). Myaamia storytelling and living well: An ethnographic examination. [Doctoral Dissertation, Iowa State University]. Iowa State University Digital Repository.

- Reimagining the Myaamia Storytelling Tradition: On Dungeons & Dragons & Diaspora (Brad Kasberg, Belt Magazine 2021)

- Eradicating the e-Word: Musings on Myaamia Language Reclamation (Wesley Y. Leonard, World Literature Today 2019)

- Tending the Fire (Julia Arwine, The Miami Student Magazine 2018)

Tribal Resources

- Official Website for the Delaware Tribe of Indians

- Lenape Stories A collection of stories told by members of the Delaware Tribe and Delaware Nation

- Lenape Clothing Information about clothing, dress, ribbonwork, beadwork, and more

- Lenape Talking Dictionary Online tool with an expansive dictionary and language lessons to support Lenape language education

- Removal History of the Delaware Tribe

- Delaware Nation Cultural Preservation

- Lenape Center A nonprofit organization fiscally sponsored by the New York Foundation for the Arts

Books

- Recommended Reading (Nanticoke and Lenape Confederation)

-

Almighty Voice and His Wife by

ISBN: 9780887548970Publication Date: 2010-04-01A modern classic about the place of First Nations people in Canada. -

Red Scare: The State's Indigenous Terrorist by

ISBN: 9780520972674Publication Date: 2021-12-03New Indigenous movements are gaining traction in North America: the Missing and Murdered Women and Idle No More movements in Canada, and the Native Lives Matter and NoDAPL movements in the United States. These do not represent new demands for social justice and treaty rights, which Indigenous groups have sought for centuries. But owing to the extraordinary visibility of contemporary activism, Indigenous people have been newly cast as terrorists--a designation that justifies severe measures of policing, exploitation, and violence. Red Scare investigates the intersectional scope of these four movements and the broader context of the treatment of Indigenous social justice movements as threats to neoliberal and imperialist social orders. In Red Scare, Joanne Barker shows how US and Canadian leaders leverage the fear-driven discourses of terrorism to allow for extreme responses to Indigenous activists, framing them as threats to social stability and national security. The activist-as-terrorist framing is cropping up everywhere, but the historical and political complexities of Indigenous movements and state responses are unique. Indigenous criticisms of state policy, resource extraction and contamination, intense surveillance, and neoliberal values are met with outsized and shocking measures of militarized policing, environmental harm, and sexual violence. -

The Turtle's Beating Heart: One Family's Story of Lenape Survival by

ISBN: 9780803294936Publication Date: 2017-01-01Low brings to light deeply held secrets of Native ancestry as she recovers the life story of her Kansas grandfather, Frank Bruner (1889-1963). She remembers her childhood in Kansas, where her grandparents remained at a distance, personally and physically, from their grandchildren, despite living only a few miles away. As an adult, she comes to understand her grandfather's Delaware (Lenape) legacy of persecution and heroic survival in the southern plains of the early 1900s, where the Ku Klux Klan attacked Native people along with other ethnic minorities. As Low unravels this hidden family history of the Lenape diaspora, she discovers the lasting impact of trauma and substance abuse, the deep sense of loss and shame related to suppressed family emotions, and the power of collective memory. In this moving exploration of her grandfather's life, the former poet laureate of Kansas evokes the beauty of the Flint Hills grasslands, the hardships her grandfather endured, and the continued discovery of his teachings. -

Long Journey Home: Oral histories of contemporary Delaware Indians by

ISBN: 9780253349682Publication Date: 2007-12-24Through first-person accounts, Long Journey Homepresents the stories of the Lenape, also known as the Delaware Tribe. These oral histories, which span the post-Civil War era to the present, are gathered into four sections and tell of personal and tribal events as they unfold over time and place. The history of the Lenape is one of forced displacement, from their original tribal home along the eastern seaboard into Pennsylvania, continuing with a series of displacements in Ohio, Indiana, Missouri, Kansas, and the Indian Territory. For the group of Lenape interviewed for this book, home is now the area around Bartlesville, Oklahoma. The stories of their long journey have been handed down and remain part of the tribe's collective memory and bring an unforgettable immediacy to the tale of the Lenape. Above all they make clear that the history of seven generations remains very much alive. -

Only Approved Indians by

ISBN: 9780806169033Publication Date: 2021-07-08In these short stories, Jack D. Forbes captures the remarkable breadth and variety of American Indian life. Drawing on his skills as scholar and native activist, and, above all, as artist, Forbes enlarges our sense of how American Indians experience themselves and the world around them. Though all the main characters are of Indian descent, each is a unique combination of tribal origin, social status, age, and life-style-from native elder and college professor to lesbian barmaid and Chicano adolescent. Nevertheless the U.S. government (and perhaps white society as a whole) narrows the definition of "Indian". -

Grandfather's Song by

ISBN: 9781475297584Publication Date: 2012-09-14A troubled Lenape Indian asks the Great Spirit for a vision. In Talking Coyote's vision, a giant who calls himself, the Keeper-of-the-animals, visits him. The Keeper tells him all the animals have been saved from mankind in the Old World the Native Americans left behind millennia ago, The Old World, man left behind to come to this world to live with their brothers and sisters the animals, birds and fish. The Keeper tells Talking Coyote that the Native peoples must come back to the Old World to help maintain balance."Grandfather's Song" is the story of the Jefferson and Cornplanter families and Talking Coyote's attempt to find his way to the Old World. Flashbacks to Lenape legends and ancient stories told around campfires tell him the path to take. -

Legends of the Delaware Indians and Picture Writing by

ISBN: 0815604874Publication Date: 1997-11-01This collection of authentic Delaware legends is an affirmation of cultural values. The stories portray moral values and are translated from (and to) the Delaware language. The book was originally published in 1905. Richard Calmit Adams, was a Lenape poet and writer. He published five books collecting Delaware stories, history, religion, and modern political perspectives. -

A Bibliography of North American Indian Mental Health by

ISBN: 0313229309Publication Date: 1981-07-24Prepared under the auspices of the White Cloud Center.

"Brings together both recent and earlier English-language literature on the mental health and variables affecting the mental health of American Indians, defined to include all North American native peoples. Listings are not limited to research studies; everything relevant is included.... Recommended for larger academic collections supporting research, and other collections where there is a special interest in Native Americans." - Review

Film

-

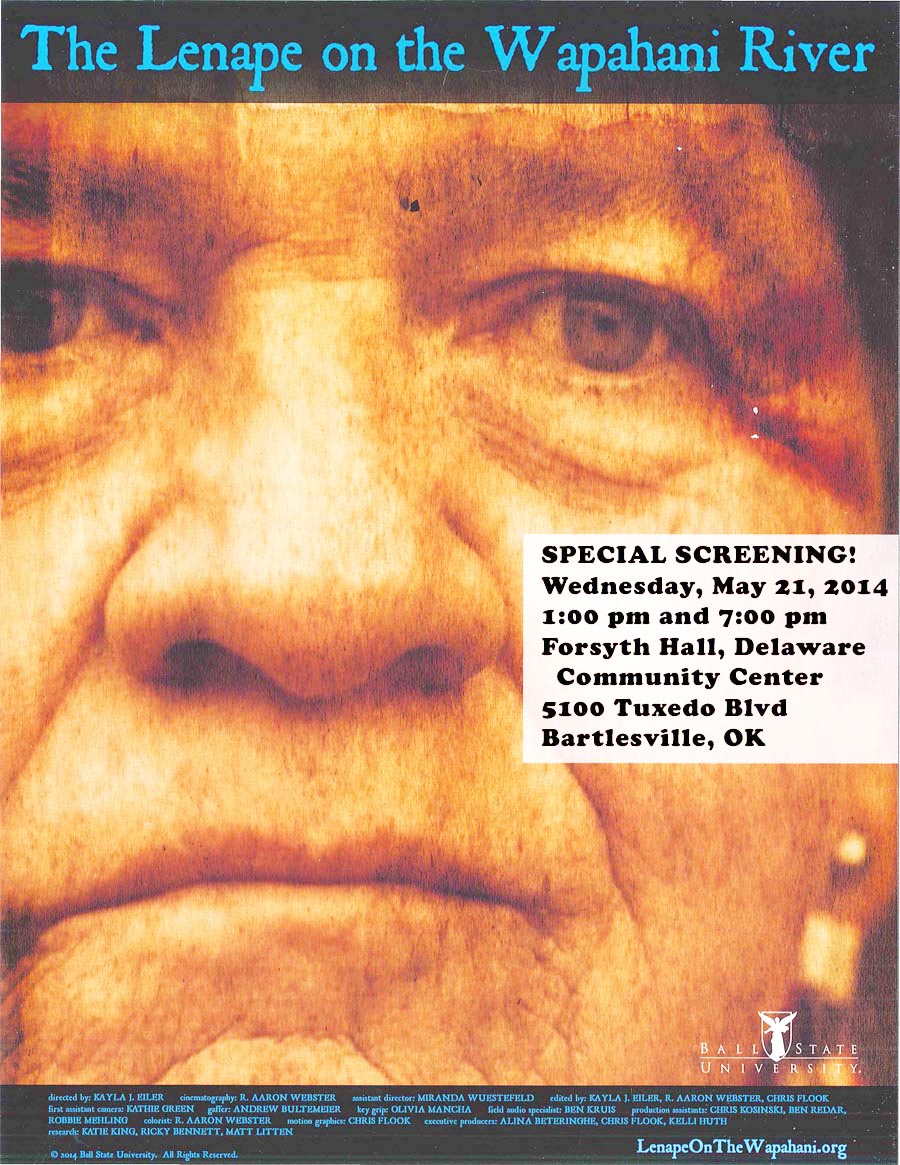

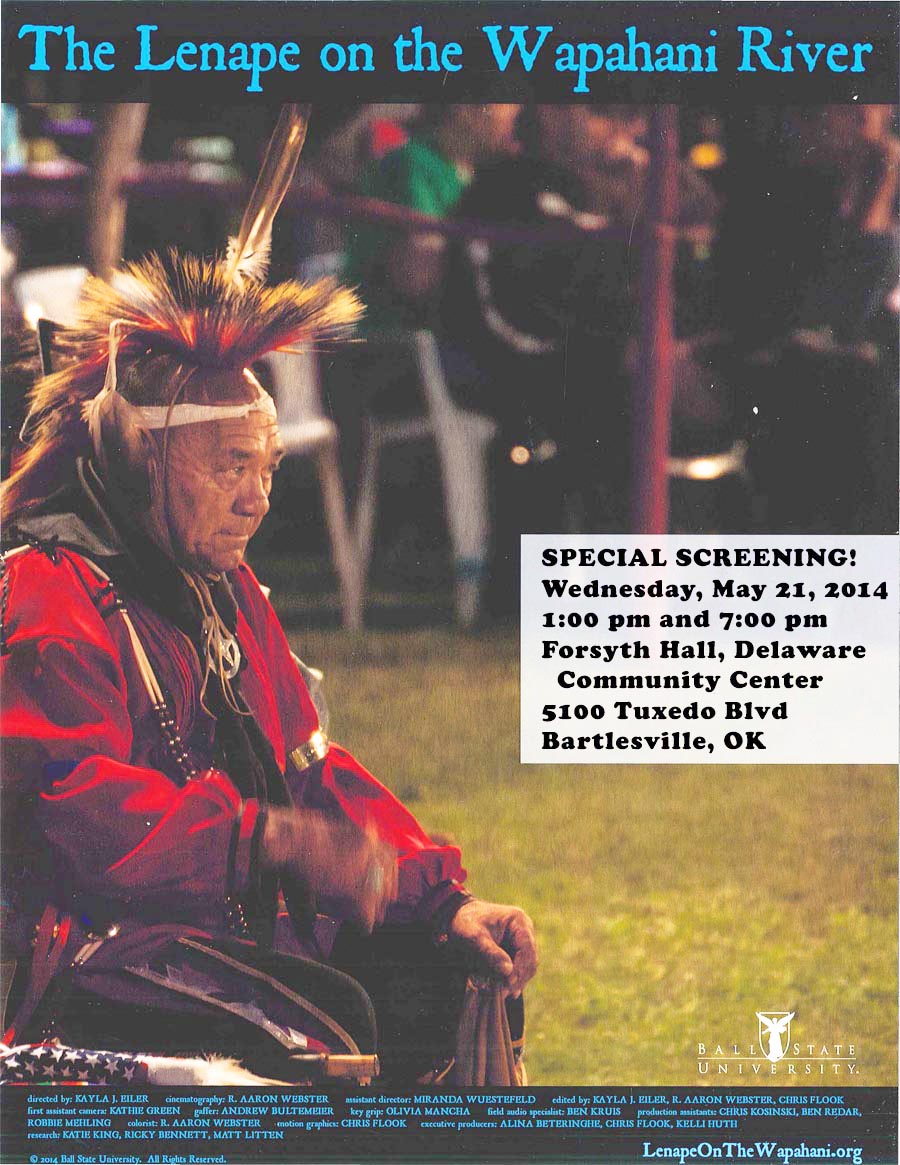

The Lenape on the Wapahani River

by

Publication Date: 2014-04-13The Lenape on the Wapahani River is an immersive learning project at Ball State University. Funded by the Hamer and Phyllis Shafer Foundation, the project seeks to provide educational resources about the Delaware (or Lenape) Native Americans during their time in East Central Indiana from the 1790s through 1821. Partnering with the Delaware Tribe of Indians and Conner Praire Interactive History Park, the documentary and associated website provide a rich and detailed look at this often overlooked story about the Delaware Native American experience in Indiana.

The Lenape on the Wapahani River

by

Publication Date: 2014-04-13The Lenape on the Wapahani River is an immersive learning project at Ball State University. Funded by the Hamer and Phyllis Shafer Foundation, the project seeks to provide educational resources about the Delaware (or Lenape) Native Americans during their time in East Central Indiana from the 1790s through 1821. Partnering with the Delaware Tribe of Indians and Conner Praire Interactive History Park, the documentary and associated website provide a rich and detailed look at this often overlooked story about the Delaware Native American experience in Indiana.

Visual Arts

-

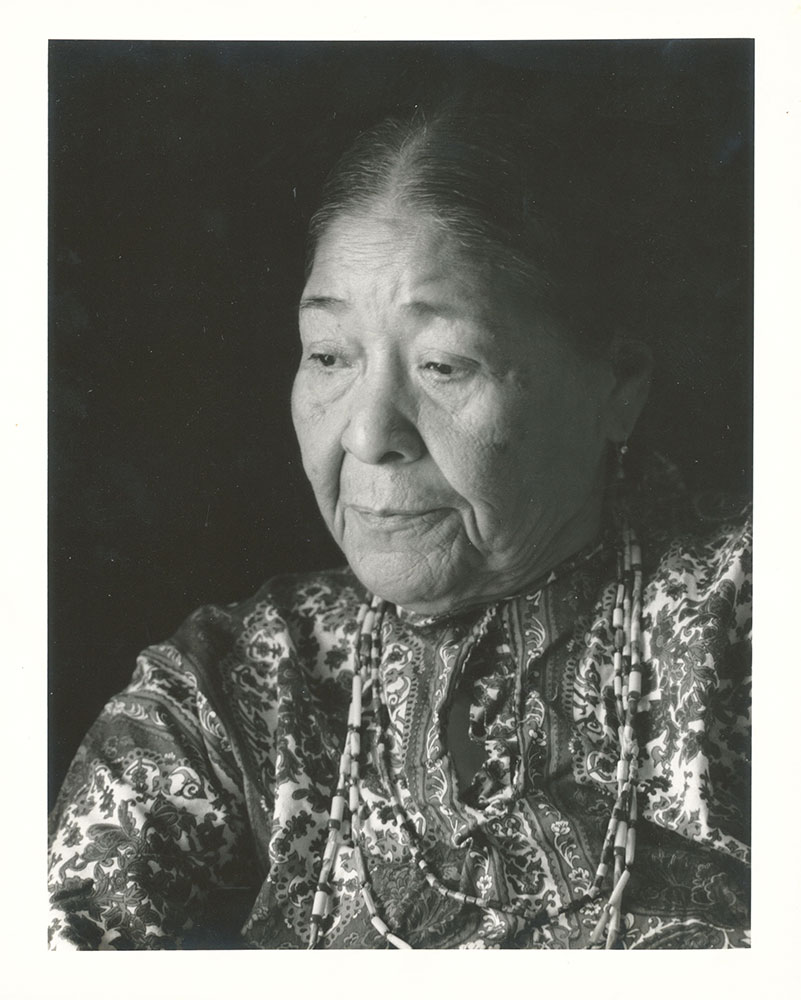

Nora Thompson Dean

Nora Thompson Dean (July 3, 1907 – November 29, 1984), also known as Weenjipahkihelexkwe (modern Unami orthography: Weènchipahkihëlèxkwe[1]), which translates as "Touching Leaves Woman" in Unami, was a member of the Delaware Tribe of Indians. As a Lenape traditionalist and one of the last fluent speakers of the southern Unami dialect of the Lenape language, she was an influential mentor to younger tribal members and is widely cited in scholarship on Lenape culture.

Nora Thompson Dean

Nora Thompson Dean (July 3, 1907 – November 29, 1984), also known as Weenjipahkihelexkwe (modern Unami orthography: Weènchipahkihëlèxkwe[1]), which translates as "Touching Leaves Woman" in Unami, was a member of the Delaware Tribe of Indians. As a Lenape traditionalist and one of the last fluent speakers of the southern Unami dialect of the Lenape language, she was an influential mentor to younger tribal members and is widely cited in scholarship on Lenape culture. -

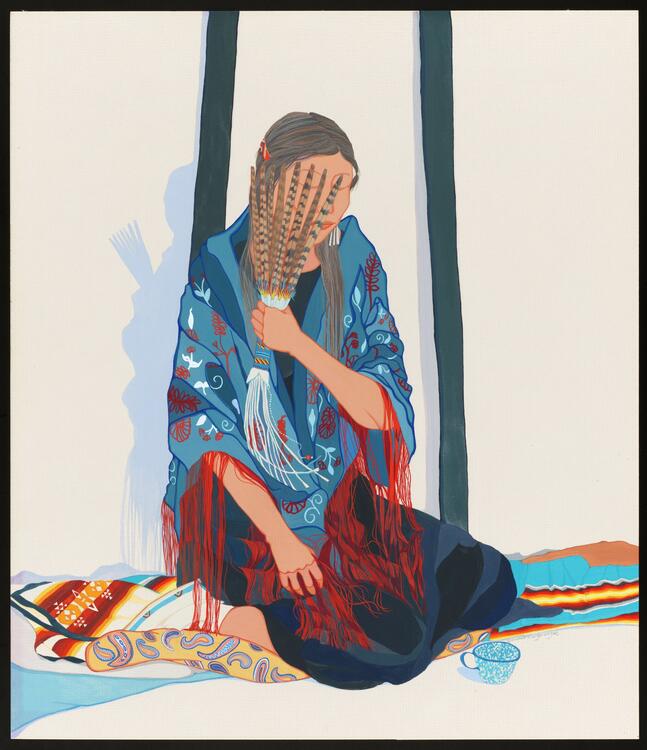

Holly Wilson

Multi-media artist Holly Wilson creates figures as her storytellers, conveying stories of the sacred and the precious, capturing moments of our day, vulnerabilities, and strengths. Holly Wilson an enrolled member of the Delaware Nation, Lenape and Descendent of the Delaware Tribe of Indians, is now based in Mustang, Oklahoma.

Holly Wilson

Multi-media artist Holly Wilson creates figures as her storytellers, conveying stories of the sacred and the precious, capturing moments of our day, vulnerabilities, and strengths. Holly Wilson an enrolled member of the Delaware Nation, Lenape and Descendent of the Delaware Tribe of Indians, is now based in Mustang, Oklahoma. -

Nathan Young

Nathan Young is an artist, scholar, and composer from Tahlequah, Oklahoma working in an expanded practice that incorporates sound, video, documentary, animation, installation, socially engaged art, and experimental and improvised music. Young’s work often engages the spiritual and the political, re-imagining indigenous sacred imagery to complicate and subvert notions of the sublime. Young is a founding and former member of the artist collective Postcommodity. Young is an enrolled member of The Delaware Tribe of Indians and is also a direct descendent of the Pawnee Nation and Kiowa Tribe.

Nathan Young

Nathan Young is an artist, scholar, and composer from Tahlequah, Oklahoma working in an expanded practice that incorporates sound, video, documentary, animation, installation, socially engaged art, and experimental and improvised music. Young’s work often engages the spiritual and the political, re-imagining indigenous sacred imagery to complicate and subvert notions of the sublime. Young is a founding and former member of the artist collective Postcommodity. Young is an enrolled member of The Delaware Tribe of Indians and is also a direct descendent of the Pawnee Nation and Kiowa Tribe.

Articles

- Wyckoff, L. L., & Zunigha, C. (1994). Delaware: honoring the past and preparing for the future. Native Peoples Magazine, 7, 56–62.

- Barker, J. (2006). Gender, Sovereignty, and the Discourse of Rights in Native Women’s Activism. Meridians, 7(1), 127–161.

- Barker, J. (2019). Confluence: Water as an Analytic of Indigenous Feminisms. American Indian Culture & Research Journal, 43(3), 1–40. https://doi-org.proxyiub.uits.iu.edu/10.17953/aicrj.43.3.barker

- Ahmed, A. K., Baker, J., & Coumans, H. (2023). Wëlamàlsëwakàn (Good Health): Reimagining the Right to Health through Lenape Epistemologies. Health and human rights, 25(1), 207–212.

- Oral History: Nora Thompson Dean interviewed by Katherine Red Corn April 1968 from the University of Oklahoma Libraries.

- Committing to the Beauty of Lenape Art: How Joe Baker reclaimed a historic artform in order to assert his Lenape identity (Benjamin Korman, The Met 2021)

- Indigenous Artistry: Leonard Harmon (National Park Service)

- Indigenous Poetry Series: Rebecca Haff Lowry

- Manhattan is a Lenape Word (Natalie Diaz, Postcolonial Love Poem 2020)

- The history of the people behind the name of Muncie and Delaware County (Grayson Joslin, Ball State Daily News 2022)

- ‘We just want to be welcomed back’: The Lenape seek a return home (Kenny Cooper, WHYY Public Radio 2021)

- Audio: Art of Native America at The Met This tour features contemporary Indigenous artists, curators, and historians, who share their perspectives on the traditions and techniques on display from the Charles and Valerie Diker Collection of Native American art.

Tribal Resources

Today, Shawnee people are enrolled in three federally recognized tribes: Absentee-Shawnee Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma, Eastern Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma, and Shawnee Tribe.

- Absentee Shawnee Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma Website

- Eastern Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma Website

- Eastern Shawnee Educator's Guide

- History

- Digital Collection (Ohio History Connection)

- The Shawnee Tribe Website

- Shawnee Nation Case Study (Native Knowledge 360)

Books

-

Replanting Cultures: Community-Engaged Scholarship in Indian Country by

ISBN: 9781438489933Publication Date: 2022-09-01Replanting Cultures provides a theoretical and practical guide to community-engaged scholarship with Indigenous communities in the United States and Canada. Chapters on the work of collaborative, respectful, and reciprocal research between Indigenous nations and colleges and universities, museums, archives, and research centers are designed to offer models of scholarship that build capacity in Indigenous communities. Replanting Cultures includes case studies of Indigenous nations from the Stó:lō of the Fraser River Valley to the Shawnee and Miami tribes of Oklahoma, Ohio, and Indiana. Native and non-Native authors provide frank assessments of the work that goes into establishing meaningful collaborations that result in the betterment of Native peoples. -

Koko's Secret Treasure by

ISBN: 9781365722202Publication Date: 2017-01-31When she overhears Koko (grandma) say that she has the GREATEST TREASURE IN THE WORLD, a little Shawnee girl goes on her own little treasure hunt to find it. What in the world could Koko be hiding? -

Instruments of the True Measure by

ISBN: 9780816538270Publication Date: 2018-10-30Instruments of the True Measure charts the coordinates and intersections of land, history, and culture. Lyrical passages map the parallel lives of ancestral figures and connect dispossessions of the past to lived experiences of the present. Shawnee history informs the collection, and Da's fascination with uncovering and recovering brings the reader deeper into the narrative of Shawnee homeland. Images of forced removal and frontier violence reveal the wrenching loss and reconfiguration of the Shawnee as a people. The body and history become lands that are measured and plotted with precise instruments. Surveying and geography underpin the collection, but even as Da' investigates these signifiers of measurement, she pushes the reader to interrogate their function within the stark atrocities of American history. -

That's What They Used to Say: Reflections on American Indian Oral Tradiations by

ISBN: 9780806157757Publication Date: 2017-10-12As a child growing up in rural Oklahoma, Donald Fixico often heard "hvmakimata"—"that's what they used to say"—a phrase Mvskokes and Seminoles use to end stories. In his latest work, Fixico, who is Shawnee, Sac and Fox, Mvskoke (as "Muskogee" is spelled in the Mvskoke language), and Seminole, invites readers into his own oral tradition to learn how storytelling, legends and prophecies, and oral histories and creation myths knit together to explain the Indian world. Interweaving the storytelling and traditions of his ancestors, Fixico conveys the richness and importance of oral culture in Native communities and demonstrates the power of the spoken word to bring past and present together, creating a shared reality both immediate and historical for Native peoples. Fixico's stories conjure war heroes and ghosts, inspire fear and laughter, explain the past, and foresee the future--and through them he skillfully connects personal, familial, tribal, and Native history. Oral tradition, Fixico affirms, at once reflects and creates the unique internal reality of each Native community. -

Inherit the Blood: Poetry and Fiction

by

ISBN: 0938410288Publication Date: 1985-06-01Shawnee/Cayuga poet and indigenous activist Barney Bush was born in Herod, Illinois. Bush was a member of the Society of Artists, Composers, and Editors of Music. His honors include a fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts. He helped establish the Institute of the Southern Plains, a Cheyenne Indian school located in Oklahoma, and helped many universities develop Native American studies programs.

Inherit the Blood: Poetry and Fiction

by

ISBN: 0938410288Publication Date: 1985-06-01Shawnee/Cayuga poet and indigenous activist Barney Bush was born in Herod, Illinois. Bush was a member of the Society of Artists, Composers, and Editors of Music. His honors include a fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts. He helped establish the Institute of the Southern Plains, a Cheyenne Indian school located in Oklahoma, and helped many universities develop Native American studies programs. -

White Bead Ceremony by

ISBN: 9780933031920Publication Date: 1995-10-01"Provides a welcome glimpse at how tribal traditions are woven into the fabric of modern-day life.” --Publishers Weekly -

Reservation Capitalism: Economic development in Indian country by

ISBN: 9781440801112Publication Date: 2012-03-09This unique book investigates the history and future of American Indian economic activities and explains why tribal governments and reservation communities must focus on creating sustainable privately and tribally owned businesses if reservation communities and tribal cultures are to continue to exist.Native American peoples suffer from health, educational, infrastructure, and social deficiencies that most Americans who live outside of tribal lands are wholly unaware of and would not tolerate. By creating sustainable economic development on reservations, however, gradual, long-term change can be effected, thereby improving the standard of living and sustaining tribal cultures. The book focuses on strategies for establishing privately and publicly owned economic activities on reservations and creating economies where reservation inhabitants can be employed, live, and buy the necessities of life, thereby enabling complete tribal self-sufficiency and self-determination. -

The Shawnee: Kohkumthena's Grandchildren by

ISBN: 1878208292Publication Date: 1994-11-01Thom takes the reader into the world of the Shawnee Indians from the beginning of their oral history to present day, as seen through the eyes of a young boy as he spends the night guarding the tribal alter and sacred items. During this time the sacred items, one by one, take him on a journey and explain their importance to his people.

Film

-

The Dead Can't Dance

by

Publication Date: 2010The directorial debut of Rodrick Pocowatchi (Comanche, Pawnee and Shawnee), The Dead Can’t Dance is about Comanche citizens Dax Wildhorse (Rodrick Pocowatchit), Ray Wildhorse (Guy Ray Pocowatchit), and Ray’s kid, Eddie Wildhorse (T.J. Williams). This comedy/ horror is about a mysterious disease that turns everyone but the Wildhorses into zombies. The group must put their squabbling and drama behind them to fight off the undead and get Eddie to college. Available for free on Tubi.

The Dead Can't Dance

by

Publication Date: 2010The directorial debut of Rodrick Pocowatchi (Comanche, Pawnee and Shawnee), The Dead Can’t Dance is about Comanche citizens Dax Wildhorse (Rodrick Pocowatchit), Ray Wildhorse (Guy Ray Pocowatchit), and Ray’s kid, Eddie Wildhorse (T.J. Williams). This comedy/ horror is about a mysterious disease that turns everyone but the Wildhorses into zombies. The group must put their squabbling and drama behind them to fight off the undead and get Eddie to college. Available for free on Tubi. -

Warrior Women

by

Publication Date: 2018In the 1970s, with the swagger of unapologetic Indianness, organizers of the American Indian Movement (AIM) fought for Native liberation and survival as a community of extended families. Warrior Women is the story of Madonna Thunder Hawk, one such AIM leader who shaped a kindred group of activists' children—including her daughter Marcy—into the "We Will Remember" Survival School as a Native alternative to government-run education. Together, Madonna and Marcy fought for Native rights in an environment that made them more comrades than mother-daughter. Today, with Marcy now a mother herself, both are still at the forefront of Native issues, fighting against the environmental devastation of the Dakota Access Pipeline and for Indigenous cultural values. Through a circular Indigenous style of storytelling, this film explores what it means to navigate a movement and motherhood and how activist legacies are passed down and transformed from generation to generation in the context of colonizing government that meets Native resistance with violence.

Warrior Women

by

Publication Date: 2018In the 1970s, with the swagger of unapologetic Indianness, organizers of the American Indian Movement (AIM) fought for Native liberation and survival as a community of extended families. Warrior Women is the story of Madonna Thunder Hawk, one such AIM leader who shaped a kindred group of activists' children—including her daughter Marcy—into the "We Will Remember" Survival School as a Native alternative to government-run education. Together, Madonna and Marcy fought for Native rights in an environment that made them more comrades than mother-daughter. Today, with Marcy now a mother herself, both are still at the forefront of Native issues, fighting against the environmental devastation of the Dakota Access Pipeline and for Indigenous cultural values. Through a circular Indigenous style of storytelling, this film explores what it means to navigate a movement and motherhood and how activist legacies are passed down and transformed from generation to generation in the context of colonizing government that meets Native resistance with violence.

Visual Arts

-

Ruthe Blalock Jones

Shawnee - Delaware - Peoria

Ruthe Blalock Jones

Shawnee - Delaware - Peoria

Director Emeritus and Associate Professor of Art, Bacone College, Muskogee, Oklahoma, since 1979. Her works focus on the traditional American Indian ceremonial and social events. They are recorded in paintings, drawings, limited edition prints in linoleum block, woodcut, and serigraphs. https://dc.library.okstate.edu/digital/collection/halloffame/id/64/ -

Inez Running-rabbit

Inez Running-rabbit was an accomplished Shawnee Native American artist. Her works include paintings, pastels, drawings, sculptures, beadwork, embroidery, quilts, clay pottery, jewelry, fetishes, dolls, and volumes of poetry. She worked full time at her craft her entire life and supported herself with her artwork. She was a hard worker, producing over 20,000 pieces of work in her lifetime. Her last piece, her death self-portrait was completed 3 days before she died. She was born March 1st 1920 and died March 12th, 2010, having lived a full life by age 90. Her unabashed, uncontrived, free thinking, creative expressions have left the world, one of the greatest treasures, yet to be known, in the history of art. - Robin Henson, Inez Running-rabbit's Son

Inez Running-rabbit

Inez Running-rabbit was an accomplished Shawnee Native American artist. Her works include paintings, pastels, drawings, sculptures, beadwork, embroidery, quilts, clay pottery, jewelry, fetishes, dolls, and volumes of poetry. She worked full time at her craft her entire life and supported herself with her artwork. She was a hard worker, producing over 20,000 pieces of work in her lifetime. Her last piece, her death self-portrait was completed 3 days before she died. She was born March 1st 1920 and died March 12th, 2010, having lived a full life by age 90. Her unabashed, uncontrived, free thinking, creative expressions have left the world, one of the greatest treasures, yet to be known, in the history of art. - Robin Henson, Inez Running-rabbit's Son -

Gibson Byrd

Gibson Byrd, a lifelong artist and educator, was known for his landscape and figurative paintings. His work emphasized social realism and auto-biographical fantasy. He highlighted human isolation, and provided commentary about social injustice. He explored his Shawnee heritage and Tulsa roots. Later in life, he rendered ethereal landscapes of rural Wisconsin and costal southern California. After teaching art at Tulsa’s Central High and Directing the Kalamazoo Art Center, he was an Art Professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison for 30 years.

Gibson Byrd

Gibson Byrd, a lifelong artist and educator, was known for his landscape and figurative paintings. His work emphasized social realism and auto-biographical fantasy. He highlighted human isolation, and provided commentary about social injustice. He explored his Shawnee heritage and Tulsa roots. Later in life, he rendered ethereal landscapes of rural Wisconsin and costal southern California. After teaching art at Tulsa’s Central High and Directing the Kalamazoo Art Center, he was an Art Professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison for 30 years. -

Ernest Spybuck

Ernest Spybuck (1883 – 1949) was an Absentee Shawnee Native American artist, who was born on the land allotted the Shawnee Indians in Indian Territory and what was to later become Pottawatomie County, Oklahoma, near the town of Tecumseh. Skybuck was an influential artist in the Native American modernism movement. -

Benjamin Harjo Jr.

Benjamin Harjo Jr. (1945 - 2023, Absentee Shawnee/Seminole) was a Native American painter and printmaker based in Oklahoma. Harjo summarized his artistic philosophy: "It has always been my contention that one's art speaks from the soul of the artist and remains viable and open to the influences of the artist's environment. Forms, colors, and movement keep it from stagnating and allow it to grow as the artist matures and develops. I feel that my art covers a wide range of emotions, from serious to humorous, and that the colors I used radiate a sense of happiness and joy."

Benjamin Harjo Jr.

Benjamin Harjo Jr. (1945 - 2023, Absentee Shawnee/Seminole) was a Native American painter and printmaker based in Oklahoma. Harjo summarized his artistic philosophy: "It has always been my contention that one's art speaks from the soul of the artist and remains viable and open to the influences of the artist's environment. Forms, colors, and movement keep it from stagnating and allow it to grow as the artist matures and develops. I feel that my art covers a wide range of emotions, from serious to humorous, and that the colors I used radiate a sense of happiness and joy."

Articles

- Fixico, D. L. (1996). Ethics and Responsibilities in Writing American Indian History. American Indian Quarterly, 20(1), 29–39. https://doi-org.proxyiub.uits.iu.edu/10.2307/1184939

- Tamburro, P. R. (2006). Ohio Valley Native Americans speak: Indigenous discourse on the continuity of identity (Vol. 67–04A.). Indiana University. Dissertation.

- Fixico, D. L. (2009). American Indian History and Writing from Home: Constructing an Indian Perspective. American Indian Quarterly, 33(4), 553–560.

- Miller, R. J. (2022). Tribal Sovereignty and Economic Efficiency versus the Courts. Washington Law Review, 97(3), 775–834.

- Barnes, B. (2023). The Intersection of Language, Law, and Sovereignty: Shawnee Perspective. Colorado Environmental Law Journal, 34(Special Issue), 17-28.

- Oral history interview with Benjamin Harjo, Jr. Interviewed by Julie Pearson Little Thunder, 2010. From Oklahoma State University Digital Collections.

- Turtle Island Storyteller Dark Rain Thom (Wisdom of the Elders Inc.)

Tribal Resources

Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians are a federally recognized Potawatomi-speaking tribe based in southwestern Michigan and northeastern Indiana.

- Citizen Potawatomi Website

- Citizen Potawatomi Nation Cultural Heritage Center

- Potawatomi Games

- Hownikan Podcast Highlighting Citizen Potawatomi Nation issues, members and more, hosted by Tribal member Paige Willett.

Books

-

O-GÎ-Mäw-Kwě Mit-I-Gwä-KÎ (Queen of the Woods) by

ISBN: 0259463140Publication Date: 2017-05-17Excerpt from O-G -M w-Kwě Mit-I-Gw -K (Queen of the Woods): Also Brief Sketch of the Algaic Language. Chief Pokagon's return home from the white man's school calls on his old friend Bertrand Requests the old man to take his mother, him self, and the family dog to some wild retreat to spend the summer. This novel was written as a testimony to the Potawatomi traditions, stability, and continuity in a rapidly changing society. -

Braiding Sweetgrass by

ISBN: 9781571313355Publication Date: 2013-10-15As a botanist and professor of plant ecology, Robin Wall Kimmerer has spent a career learning how to ask questions of nature using the tools of science. As a Potawatomi woman, she learned from elders, family, and history that the Potawatomi, as well as a majority of other cultures indigenous to this land, consider plants and animals to be our oldest teachers. In Braiding Sweetgrass, Kimmerer brings these two lenses of knowing together to reveal what it means to see humans as "the younger brothers of creation." As she explores these themes she circles toward a central argument: the awakening of a wider ecological consciousness requires the acknowledgement and celebration of our reciprocal relationship with the world. Once we begin to listen for the languages of other beings, we can begin to understand the innumerable life-giving gifts the world provides us and learn to offer our thanks, our care, and our own gifts in return. -

Dancing for Our Tribe: Potawatomi Tradition in the New Millennium by

ISBN: 9781733674423Publication Date: 2022-08-16In the heyday of the Anishinaabe Confederacy, the Potawatomis spread across Canada, Michigan, Indiana, Illinois, and Wisconsin. Pressured by the westward expansion of the fledgling United States of America, they became the most treatied of any Indian tribe. Beginning with Citizen Potawatomi Nation, photographer and Citizen Potawatomi Sharon Hoogstraten visited all nine nations of the scattered Potawatomi tribe to construct a permanent record of present-day Potawatomis wearing the traditional regalia passed down through the generations, modified to reflect the influence and storytelling of contemporary life. With more than 150 formal portraits and handwritten statements, Dancing for Our Tribe portrays the fresh reality of today's Native descendants and their regalia: people who live in a world of assimilation, sewing machines, polyester fabrics, duct tape, tattoos, favorite sports teams, proud military service, and high-resolution digital cameras. -

Potawatomi Tracks: The Ballad of Vietnam and Other Stories by

ISBN: 9781933037578Publication Date: 2005-01-01Potawatomi Tracks: The Ballad of Vietnam and Other Stories is Larry Mitchell's poetic chronicle relating the events of his year-long combat tour of duty in Vietnam and the path back to his home on the Prairie Band Potawatomi Reservation in Kansas. His return from the war was followed by years of drug use, alcoholism, homelessness and racial discrimination. Potawatomi Tracks is the story of how Larry was able to overcome his feelings of despair to regain his dignity, self-respect, and take back control of his life. -

Too Close to the Sun by

ISBN: 9781543466348Publication Date: 2017-11-29This is a book of poetry, with a few anecdotes at the end. It is derived from a variety of lifetime experiences. Jacobs' poetry and anecdotes cover a variety of subjects and sensory experiences: fighting fires, the scent of sandalwood, love, gun control, current events and musicians are just a few. Some are funny and lighthearted; others are almost morose and thought-provoking. The book elicits a spectrum of human emotions that come from a lifetime of Jacobs’ learned knowledge. -

Living Resistance: An Indigenous Vision for Seeking Wholeness Every Day by

ISBN: 9781587435713Publication Date: 2023-03-07In an era in which "resistance" has become tokenized, Indigenous author Kaitlin Curtice reclaims it as a basic human calling. We each have a role to play in the world right where we are, and our everyday acts of resistance hold us all together. -

Imprints: The Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians and the City of Chicago by

ISBN: 9781609174750Publication Date: 2016-02-01The Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians has been a part of Chicago since its founding. In very public expressions of indigeneity, they have refused to hide in plain sight or assimilate. Instead, throughout the city's history, the Pokagon Potawatomi Indians have openly and aggressively expressed their refusal to be marginalized or forgotten--and in doing so, they have contributed to the fabric and history of the city. Imprints: The Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians and the City of Chicago examines the ways some Pokagon Potawatomi tribal members have maintained a distinct Native identity, their rejection of assimilation into the mainstream, and their desire for inclusion in the larger contemporary society without forfeiting their "Indianness." Mindful that contact is never a one-way street, Low also examines the ways in which experiences in Chicago have influenced the Pokagon Potawatomi. -

Corn Dance: Inspired First American Cuisine by

ISBN: 9780806190785Publication Date: 2023-10-03Growing up in Shawnee, Oklahoma, among a host of grandmothers and aunties, Loretta Barrett Oden learned the lessons and lore of Potawatomi cooking, along with those of her father's family, whose ancestors arrived on the Mayflower. This rich cultural blend came to bear in the iconic restaurant she opened in Santa Fe, the Corn Dance Café, where many of the dishes in this book had their debut, setting Loretta on her path to fame as one of the most influential Native chefs in the nation, a leader in the new Indigenous food movement, and, with her Emmy Award-winning PBS series, Seasoned with Spirit: A Native Cook's Journey, a cross-cultural ambassador for First American cuisine. Corn Dance: Inspired First American Cuisine tells the story of Loretta's journey and of the dishes she created along the way. Alongside recipes that combine the flavors of her Oklahoma upbringing and Indigenous heritage with the Southwest flair of her Santa Fe restaurant, Loretta offers entertaining and edifying observations about ingredients and cooking culture. What kind of quail might turn up in your vicinity, for instance; what to do with piñon nuts, sumac, or nopales (cactus paddles); when to add a bundle of pine needles or a small branch of cedar to your braise: these and many practical words of wisdom about using the fruits of the forest, stream, or plain, accompany Loretta's insights on everything from the dubious provenance of fry bread to the Potawatomi legend behind the Three Sisters--corn, beans, and squash, the namesake ingredients of Three Sisters and Friends Salad, served at Corn Dance Café and now at Thirty Nine Restaurant at First Americans Museum in Oklahoma City, where Oden is the Chef Consultant. Amply illustrated and adapted to bring the taste of Native tradition into the home kitchen, Corn Dance invites readers to join Loretta Oden on her inspiring journey into the Indigenous heritage, and the exhilarating culinary future, of North America.

Film

-

Smoke That Travels

by

Publication Date: 2017What does it mean to be Native American today? To answer this question, filmmaker Kayla Briët explores her Prairie Band Potawatomi roots through the teachings of her father, Gary Wis-ki-ge-amatyuk. This hypnotic and introspective short film captures part of her childhood and confronts the fear of her cultural identity fading with time. Weaving together the history, language, dance, and music of her tribe, Kayla Briët's Smoke That Travels keeps her family's heritage alive and celebrates the beauty of culture.

Smoke That Travels

by

Publication Date: 2017What does it mean to be Native American today? To answer this question, filmmaker Kayla Briët explores her Prairie Band Potawatomi roots through the teachings of her father, Gary Wis-ki-ge-amatyuk. This hypnotic and introspective short film captures part of her childhood and confronts the fear of her cultural identity fading with time. Weaving together the history, language, dance, and music of her tribe, Kayla Briët's Smoke That Travels keeps her family's heritage alive and celebrates the beauty of culture. -

Like Birds in a Wind Storm

by

Publication Date: 2016Potawatomi descendants of forced removal in 1838 retrace the trail of their ancestors and discover unexpected receptions along the way.

Like Birds in a Wind Storm

by