Introduction to Artificial Intelligence

Artificial intelligence (AI) refers to a set of technologies which enable computers to perform advanced functions that are typically thought to require human intelligence. These functions might include recognizing faces, analyzing data, driving cars, creating art, interpreting and generating written and spoken language, and more. AI systems are trained on vast amounts of data, allowing them to identify patterns and relationships which humans may not be able to see. The AI learning process often involves algorithms, which are sets of rules or instructions that guide an AI's analysis and decision-making. Through continuous learning and adaptation, AI systems have become increasingly adept at performing tasks, from recognizing images to translating languages and beyond.

This guide contains a selection of resources that can help teachers and students learn about AI, literacy, and ways to navigate AI in classroom settings, giving us all a strong foundation to ethically and responsibly use AI technologies.

Suggested introductory articles:

- What is AI? Everyone thinks they know but no one can agree. And that’s a problem (Will Douglas Heaven; MIT Technology Review)

- Humans Are Biased. Generative AI Is Even Worse (Leonardo Nicoletti and Dina Bass, Bloomberg Technology + Equality)

- AI Literacy: A Framework to Understand, Evaluate, and Use Emerging Technology (Keun-woo Lee, Kelly Mills, Pati Ruiz, Merijke Coenraad, Judi Fusco, Jeremy Roschelle and Josh Weisgrau, Digital Promise)

- A.I. Can Now Create Lifelike Videos. Can You Tell What’s Real? (Stuart A. Thompson, New York Times)

Sources: AI Literacy: A Framework to Understand, Evaluate, and Use Emerging Technology (Keun-woo Lee, Kelly Mills, Pati Ruiz, Merijke Coenraad, Judi Fusco, Jeremy Roschelle and Josh Weisgrau; Digital Promise, June 18, 2024); What is Artificial Intelligence (AI)? (Google Cloud); What is AI? Everyone thinks they know but no one can agree. And that’s a problem (Will Douglas Heaven; MIT Technology Review, July 10, 2024)

You've probably been hearing a lot about artificial intelligence (AI)—but what is it exactly? As stated in the previous tab, artificial intelligence is a term that refers to technologies that are thought to require human intelligence. Though it might feel like AI had only recently been brought into our lives, it has actually been around since the 1950s. The Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence (known as the Dartmouth Workshop) was a 1956 summer workshop widely considered to be the founding event of artificial intelligence as a field.

Image: Participants at the Dartmouth Workshop. The Minsky Family (1956).

In the 1980s, "expert systems" (programs that answer questions or solve problems about a specific domain of knowledge) became widely used by corporations around the world to streamline processes like ordering computer systems and identifying compounds in spectrometer readings. In the 2000s, AI were trained on big data, leading to new systems that could perform tasks such as facial recognition, natural language processing, answer trivia questions (remember IBM's Waston?), and more.

Image: IBM's Watson competing on Jeopardy in 2011.

Since 2020, we have been in an "AI Boom" era, following the release of large language models exhibiting human-like traits of knowledge, attention and creativity such as ChatGPT. For more on the current state of AI, check out the following video:

Video: How will AI change the world? Ted-ED (2022). Stuart Russell discusses the current limitations of artificial intelligence and the possibility of creating human-compatible technology.

Articles

-

Artificial General Intelligence Is Already Here (Blaise Agüera y Arcas and Peter Norvig, NOEMA)Today’s most advanced AI models have many flaws, but decades from now, they will be recognized as the first true examples of artificial general intelligence.

-

Machines Like Us (Grace Huckins, MIT Technology Review)Philosophers, cognitive scientists, and engineers are grappling with what it would take for AI to become conscious.

-

AI's Inequality Problem (David Rotman, MIT Technology Review)New digital technologies are exacerbating inequality. Here’s how scientists creating AI can make better choices.

-

Making AI into Jobs (David Rotman, MIT Technology Review)Can AI, advanced robotics, self-driving cars, and other recent breakthroughs spread prosperity to the population at large?

Sources: "History of artificial intelligence" & "Dartmouth Workshop" (Wikipedia)

There is a long history of depicting artificial beings in literature. Even in antiquity, thinkers and alchemists were imagining artificial beings endowed with intelligence or consciousness by master craftsmen. The books listed below are in chronological order beginning in the 1800s and highlight some pivotal moments of AI in fiction.

-

Frankenstein by

ISBN: 9780141439471Publication Date: 1818Obsessed by creating life itself, Victor Frankenstein plunders graveyards for the material to fashion a new being, which he shocks into life by electricity. But his botched creature, rejected by Frankenstein and denied human companionship, sets out to destroy his maker and all that he holds dear. Mary Shelley's chilling gothic tale was conceived when she was only eighteen, living with her lover Percy Shelley near Byron's villa on Lake Geneva. It would become the world's most famous work of horror fiction, and remains a devastating exploration of the limits of human creativity. -

Erewhon by

ISBN: 0140430571Publication Date: 1872Setting out to make his fortune in a far-off country, a young traveller discovers the remote and beautiful land of Erewhon and is given a home among its extraordinarily handsome citizens. But their visitor soon discovers that this seemingly ideal community has its faults - here crime is treated indulgently as a malady to be cured, while illness, poverty and misfortune are cruelly punished, and all machines have been superstitiously destroyed after a bizarre prophecy. Can he survive in a world where morality is turned upside down? Inspired by Samuel Butler's years in colonial New Zealand and by his reading of Darwin's Origin of Species, Erewhon (1872) is a highly original, irreverent and humorous satire on conventional virtues, religious hypocrisy and the unthinking acceptance of beliefs. -

Rossum's Universal Robots by

ISBN: 9781843914594Publication Date: 1920Seen as a precursor to works such as Huxley's Brave New World, this true classic of the dystopian genre remains all too resonant in today's political climate. Determined to liberate the mass-produced but highly intelligent robots forged in the machinery of Rossum's island factory, Helena Glory arrives in a blaze of righteousness only to find herself perplexed and set aback by the robots' seeming humanity but absolute lack of sentience. Drawing huge international attention following its original publication in 1921, Rossum's Universal Robots was a strikingly prescient meditation on the themes of humanity and subjugation that were to dominate the 20th century. This work is also famed as being the first ever use of the word "robot." -

The Humanoids by

ISBN: 0312852533Publication Date: 1948On the far planet Wing IV, a brilliant scientist creates the humanoids--sleek black androids programmed to serve humanity. But are they perfect servants--or perfect masters? Slowly the humanoids spread throughout the galaxy, threatening to stifle all human endeavor. Only a hidden group of rebels can stem the humanoid tide...if it's not already too late. Fist published in Astounding Science Fiction during the magazine's heyday, The Humanoids--sceince fiction grand master Jack Williamson's finest novel--has endured for fifty years as a classic on the theme of natural versus artificial life. -

Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? by

ISBN: 9780345404473Publication Date: 1968A masterpiece ahead of its time, a prescient rendering of a dark future, and the inspiration for the blockbuster film Blade Runner. By 2021, the World War has killed millions, driving entire species into extinction and sending mankind off-planet. Those who remain covet any living creature, and for people who can't afford one, companies built incredibly realistic simulacra: horses, birds, cats, sheep. They've even built humans. Immigrants to Mars receive androids so sophisticated they are indistinguishable from true men or women. Fearful of the havoc these artificial humans can wreak, the government bans them from Earth. Driven into hiding, unauthorized androids live among human beings, undetected. Rick Deckard, an officially sanctioned bounty hunter, is commissioned to find rogue androids and "retire" them. But when cornered, androids fight back—with lethal force. -

Neuromancer by

ISBN: 9780441007462Publication Date: 1984Winner of the Hugo, Nebula, and Philip K. Dick Awards, Neuromancer is a science fiction masterpiece--a classic that ranks as one of the twentieth century's most potent visions of the future. Case was the sharpest data-thief in the matrix--until he crossed the wrong people and they crippled his nervous system, banishing him from cyberspace. Now a mysterious new employer has recruited him for a last-chance run at an unthinkably powerful artificial intelligence. With a dead man riding shotgun and Molly, a mirror-eyed street-samurai, to watch his back, Case is ready for the adventure that upped the ante on an entire genre of fiction. Neuromancer was the first fully-realized glimpse of humankind's digital future--a shocking vision that has challenged our assumptions about technology and ourselves, reinvented the way we speak and think, and forever altered the landscape of our imaginations. -

The Lifecycle of Software Objects by

ISBN: 9781596063174Publication Date: 2010-07-31The story of two people and the artificial intelligences they helped create, following them for more than a decade as they deal with the upgrades and obsolescence that are inevitable in the world of software. At the same time, it's an examination of the difference between processing power and intelligence, and of what it means to have a real relationship with an artificial entity. -

Ancillary Justice by

ISBN: 9780316246620Publication Date: 2013-10-01Winner of the Hugo, Nebula, and Arthur C. Clarke Awards: This record-breaking novel follows a warship trapped in a human body on a quest for revenge. On a remote, icy planet, the soldier known as Breq is drawing closer to completing her quest. Once, she was the Justice of Toren--a colossal starship with an artificial intelligence linking thousands of soldiers in the service of the Radch, the empire that conquered the galaxy. Now, an act of treachery has ripped it all away, leaving her with one fragile human body, unanswered questions, and a burning desire for vengeance. -

Klara and the Sun by

ISBN: 9780593318171Publication Date: 2021-03-02Here is the story of Klara, an Artificial Friend with outstanding observational qualities, who, from her place in the store, watches carefully the behavior of those who come in to browse, and of those who pass on the street outside. She remains hopeful that a customer will soon choose her. Klara and the Sun is a thrilling book that offers a look at our changing world through the eyes of an unforgettable narrator, and one that explores the fundamental question: what does it mean to love?

For more films, see Wikipedia's list of artificial intelligence films or this list on Letterboxd.

-

The Invisible Boy

by

Publication Date: 1957Timmie, a mischievous 10-year-old boy, is plopped in front of a supercomputer by his scientist father, Dr. Tom (Philip Abbott). The computer, however, secretly gives Timmie super-intelligence and he's soon able to reanimate a robot named Robbie. Timmie and Robbie become best friends, but when Robbie starts taking orders from the evil supercomputer, Timmie must choose between his best friend and the safety of the world. Available to rent on Prime and AppleTV.

The Invisible Boy

by

Publication Date: 1957Timmie, a mischievous 10-year-old boy, is plopped in front of a supercomputer by his scientist father, Dr. Tom (Philip Abbott). The computer, however, secretly gives Timmie super-intelligence and he's soon able to reanimate a robot named Robbie. Timmie and Robbie become best friends, but when Robbie starts taking orders from the evil supercomputer, Timmie must choose between his best friend and the safety of the world. Available to rent on Prime and AppleTV. -

2001: A Space Odyssey

by

Publication Date: 1968An imposing black structure provides a connection between the past and the future in this enigmatic adaptation of a short story by revered sci-fi author Arthur C. Clarke. When Dr. Dave Bowman and other astronauts are sent on a mysterious mission, their ship's computer system, HAL, begins to display increasingly strange behavior, leading up to a tense showdown between man and machine that results in a mind-bending trek through space and time. Available to stream on Max, Hulu, and Prime.

2001: A Space Odyssey

by

Publication Date: 1968An imposing black structure provides a connection between the past and the future in this enigmatic adaptation of a short story by revered sci-fi author Arthur C. Clarke. When Dr. Dave Bowman and other astronauts are sent on a mysterious mission, their ship's computer system, HAL, begins to display increasingly strange behavior, leading up to a tense showdown between man and machine that results in a mind-bending trek through space and time. Available to stream on Max, Hulu, and Prime. -

Silent Running

by

Publication Date: 1972After the end of all botanical life on Earth, ecologist Freeman Lowell maintains a greenhouse on a space station in order to preserve various plants for future generations. Assisted by three robots and a small human crew, Lowell rebels when he is ordered to destroy the greenhouse in favor of carrying cargo, a decision that puts him at odds with everyone but his mechanical companions. Lowell and his robots are forced to do anything necessary to keep their invaluable greenery alive. Available to rent on Youtube, Prime, and AppleTV.

Silent Running

by

Publication Date: 1972After the end of all botanical life on Earth, ecologist Freeman Lowell maintains a greenhouse on a space station in order to preserve various plants for future generations. Assisted by three robots and a small human crew, Lowell rebels when he is ordered to destroy the greenhouse in favor of carrying cargo, a decision that puts him at odds with everyone but his mechanical companions. Lowell and his robots are forced to do anything necessary to keep their invaluable greenery alive. Available to rent on Youtube, Prime, and AppleTV. -

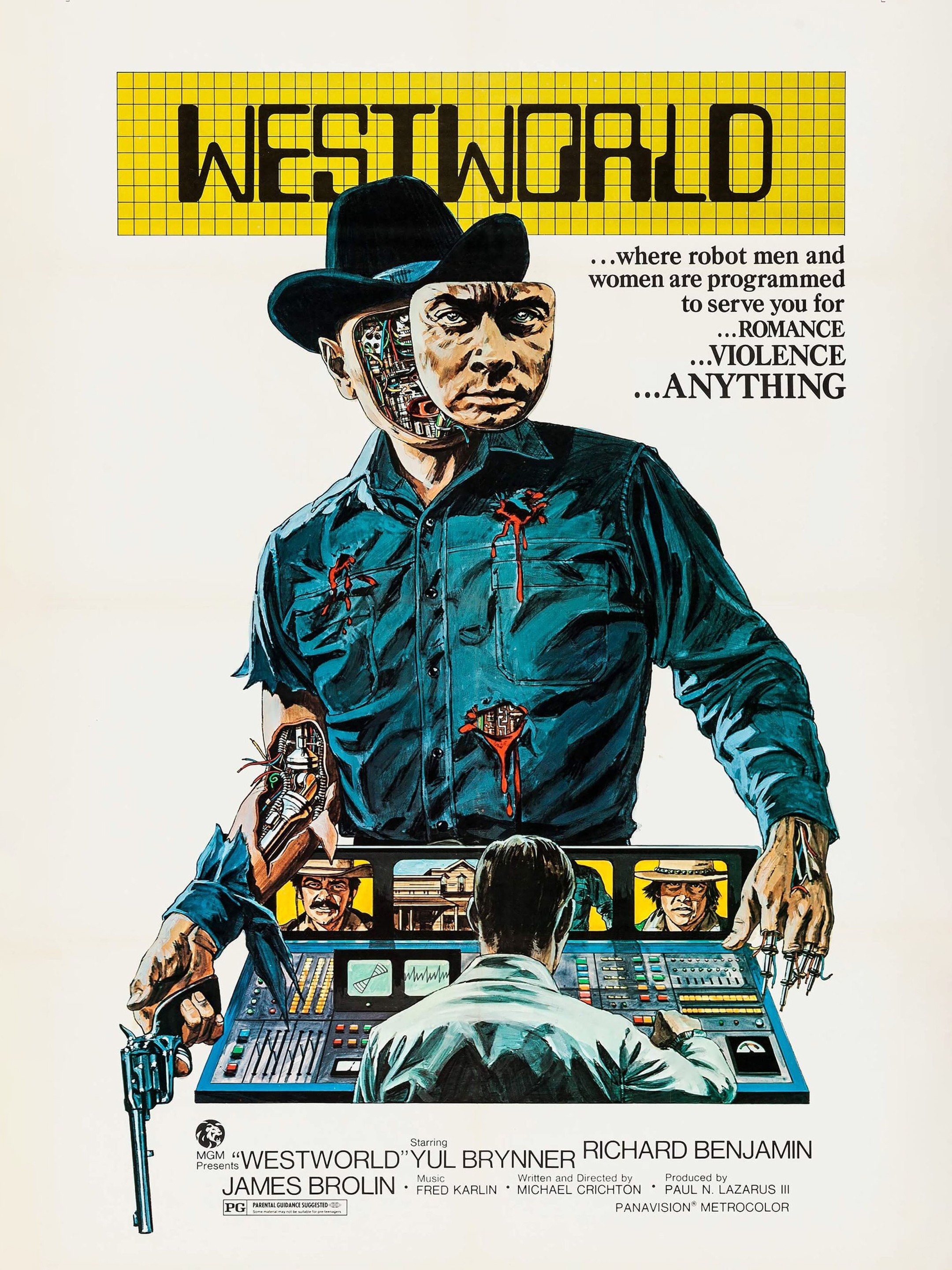

Westworld

by

Publication Date: 1973Westworld is a futuristic theme park where paying guests can pretend to be gunslingers in an artificial Wild West populated by androids. After paying a sizable entrance fee, Blane and Martin are determined to unwind by hitting the saloons and shooting off their guns. But when the system goes haywire and Blane is killed in a duel with a robotic gunslinger, Martin's escapist fantasy suddenly takes on a grim reality. Available to stream on Prime, Apple TV, YouTube, and Roku.

Westworld

by

Publication Date: 1973Westworld is a futuristic theme park where paying guests can pretend to be gunslingers in an artificial Wild West populated by androids. After paying a sizable entrance fee, Blane and Martin are determined to unwind by hitting the saloons and shooting off their guns. But when the system goes haywire and Blane is killed in a duel with a robotic gunslinger, Martin's escapist fantasy suddenly takes on a grim reality. Available to stream on Prime, Apple TV, YouTube, and Roku. -

Blade Runner

by

Publication Date: 1982Deckard (Harrison Ford) is forced by the police Boss (M. Emmet Walsh) to continue his old job as Replicant Hunter. His assignment: eliminate four escaped Replicants from the colonies who have returned to Earth. Before starting the job, Deckard goes to the Tyrell Corporation and he meets Rachel, a Replicant girl he falls in love with. Available to rent on Amazon, Apple TV, and YouTube.

Blade Runner

by

Publication Date: 1982Deckard (Harrison Ford) is forced by the police Boss (M. Emmet Walsh) to continue his old job as Replicant Hunter. His assignment: eliminate four escaped Replicants from the colonies who have returned to Earth. Before starting the job, Deckard goes to the Tyrell Corporation and he meets Rachel, a Replicant girl he falls in love with. Available to rent on Amazon, Apple TV, and YouTube. -

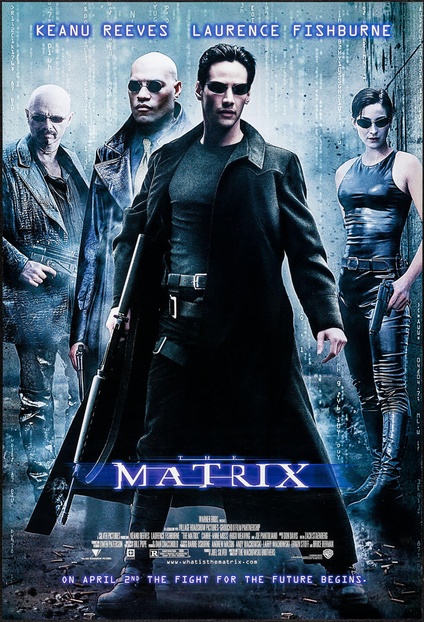

The Matrix

by

Publication Date: 1999Neo (Keanu Reeves) believes that Morpheus (Laurence Fishburne), an elusive figure considered to be the most dangerous man alive, can answer his question: What is the Matrix? Neo is contacted by Trinity (Carrie-Anne Moss), a beautiful stranger who leads him into an underworld where he meets Morpheus. They fight a brutal battle for their lives against a cadre of viciously intelligent secret agents. It is a truth that could cost Neo something more precious than his life. Available to rent on Apple, YouTube, and Amazon.

The Matrix

by

Publication Date: 1999Neo (Keanu Reeves) believes that Morpheus (Laurence Fishburne), an elusive figure considered to be the most dangerous man alive, can answer his question: What is the Matrix? Neo is contacted by Trinity (Carrie-Anne Moss), a beautiful stranger who leads him into an underworld where he meets Morpheus. They fight a brutal battle for their lives against a cadre of viciously intelligent secret agents. It is a truth that could cost Neo something more precious than his life. Available to rent on Apple, YouTube, and Amazon. -

Wall-E by

Publication Date: 2008After hundreds of lonely years, a waste management robot finds a new purpose in life. With only a cockroach for a friend, he finds true love in another robot sent on a mission to Earth to see if it is safe for human life. -

Moon

by

Publication Date: 2009Astronaut Sam Bell's (Sam Rockwell) three-year shift at a lunar mine is finally coming to an end, and he's looking forward to his reunion with his wife (Dominique McElligott) and young daughter. Suddenly, Sam's health takes a drastic turn for the worse. He suffers painful headaches and hallucinations, and almost has a fatal accident. He meets what appears to be a younger version of himself, possibly a clone. With time running out, Sam must solve the mystery before the company crew arrives.

Moon

by

Publication Date: 2009Astronaut Sam Bell's (Sam Rockwell) three-year shift at a lunar mine is finally coming to an end, and he's looking forward to his reunion with his wife (Dominique McElligott) and young daughter. Suddenly, Sam's health takes a drastic turn for the worse. He suffers painful headaches and hallucinations, and almost has a fatal accident. He meets what appears to be a younger version of himself, possibly a clone. With time running out, Sam must solve the mystery before the company crew arrives. -

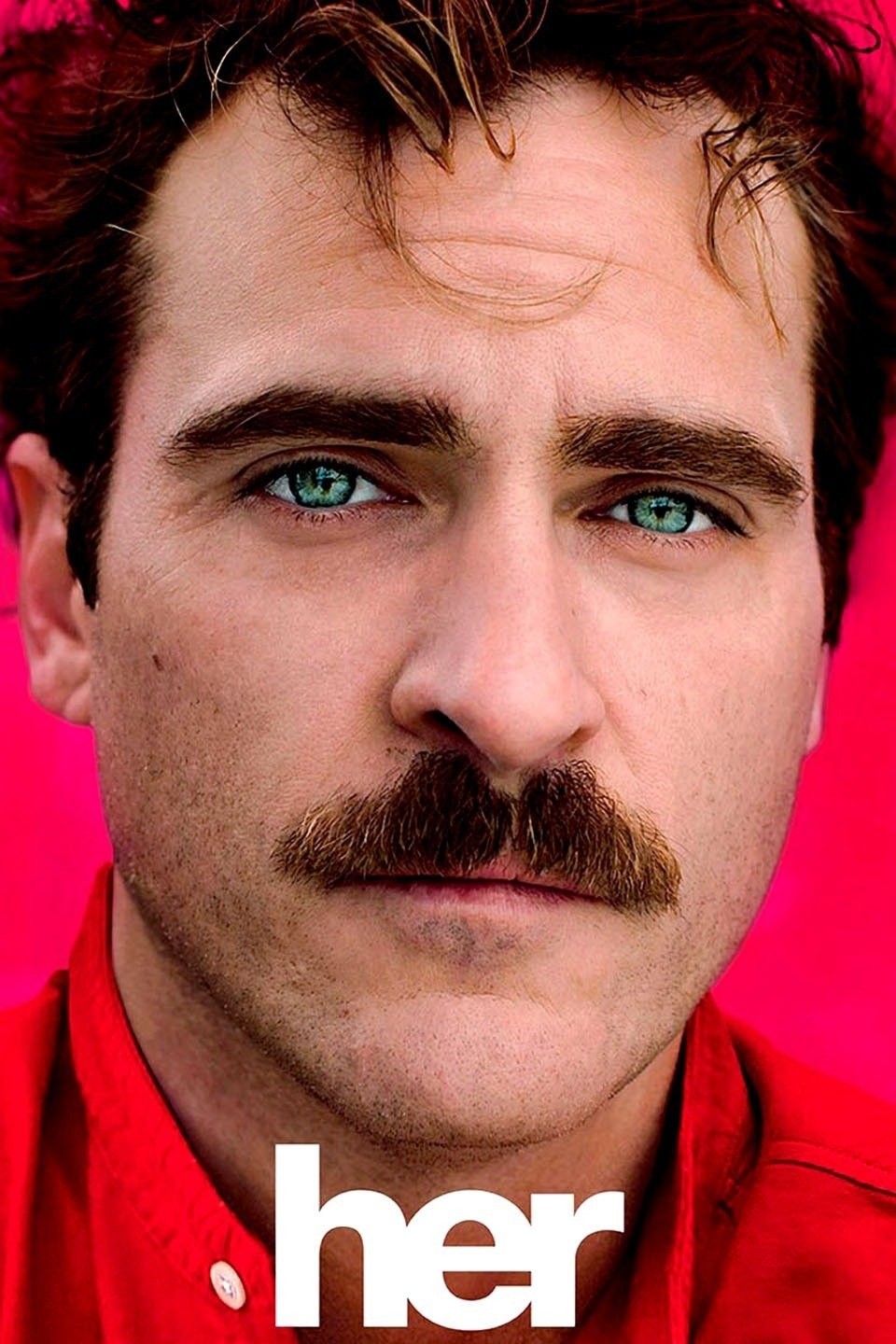

Her

by

Publication Date: 2013A sensitive and soulful man earns a living by writing personal letters for other people. Left heartbroken after his marriage ends, Theodore (Joaquin Phoenix) becomes fascinated with a new operating system which reportedly develops into an intuitive and unique entity in its own right. He starts the program and meets "Samantha" (Scarlett Johansson), whose bright voice reveals a sensitive, playful personality. Though "friends" initially, the relationship soon deepens into love. Available to stream on Max, Hulu, Amazon, and YouTube.

Her

by

Publication Date: 2013A sensitive and soulful man earns a living by writing personal letters for other people. Left heartbroken after his marriage ends, Theodore (Joaquin Phoenix) becomes fascinated with a new operating system which reportedly develops into an intuitive and unique entity in its own right. He starts the program and meets "Samantha" (Scarlett Johansson), whose bright voice reveals a sensitive, playful personality. Though "friends" initially, the relationship soon deepens into love. Available to stream on Max, Hulu, Amazon, and YouTube. -

Ex Machina

by

Publication Date: 2015Caleb Smith (Domhnall Gleeson) a programmer at a huge Internet company, wins a contest that enables him to spend a week at the private estate of Nathan Bateman (Oscar Isaac), his firm's brilliant CEO. When he arrives, Caleb learns that he has been chosen to be the human component in a Turing test to determine the capabilities and consciousness of Ava (Alicia Vikander), a beautiful robot. However, it soon becomes evident that Ava is far more self-aware and deceptive than either man imagined. Available to rent on YouTube, Apple, and Amazon.

Ex Machina

by

Publication Date: 2015Caleb Smith (Domhnall Gleeson) a programmer at a huge Internet company, wins a contest that enables him to spend a week at the private estate of Nathan Bateman (Oscar Isaac), his firm's brilliant CEO. When he arrives, Caleb learns that he has been chosen to be the human component in a Turing test to determine the capabilities and consciousness of Ava (Alicia Vikander), a beautiful robot. However, it soon becomes evident that Ava is far more self-aware and deceptive than either man imagined. Available to rent on YouTube, Apple, and Amazon. -

After Yang

by

Publication Date: 2022When his young daughter's beloved companion, an android named Yang, malfunctions, Jake searches for a way to repair it. In the process, Jake discovers the life that has been passing before him as he reconnects with his wife and daughter. Available to stream on Amazon.

After Yang

by

Publication Date: 2022When his young daughter's beloved companion, an android named Yang, malfunctions, Jake searches for a way to repair it. In the process, Jake discovers the life that has been passing before him as he reconnects with his wife and daughter. Available to stream on Amazon.

AI Software

A generative AI system creates new text, images, or other media in response to prompts. As a student, it is important to take caution when utilizing AI software, especially for coursework or when importing data. To help you ethically and responsibly engage with these tools (especially generative ones), see the AI literacy box below and read through the acceptable uses of generative AI services at IU prepared by University Information Technology Services (UITS). Always ask your professor or TA if you are using AI for a class assignment.

The remainder of this box contains a collection of software (all with free trial or free tier options). We have focused on AI that can assist with productivity, task management, studying, and organizing your work and personal life, rather than generative AI.

AI Library Tools

- Databases with AI Research Tools A collection of the Libraries' licensed databases with AI research tools enabled. Please note that some tools are in beta and may be removed from databases without warning.

AI Software at IU

- Microsoft Copilot Available for use by faculty, staff, and students aged 18 and older, and is the recommended way to use generative AI within the IU environment. Copilot is approved to interact with University-Internal data. You must be logged in with your IU email to ensure you're using Microsoft 365 at IU rather than the consumer-based Copilot service. To date, no other generative AI tools have been approved for data beyond Public classification. Copilot is built on the same AI models and data as ChatGPT-4, so you can use it to write and summarize content, create code, and answer complex questions. Copilot also has access to current internet data, enabling it to provide real-time responses to current events (a feature not available in ChatGPT, which is based on data up to 2021).

- AIU Toolkit The AIU Toolkit allows developers to directly use Azure services like Azure OpenAI to quickly develop generative AI experiences with a diverse set of prebuilt and curated models from OpenAI Meta and beyond.

-

Adobe Firefly As part of IU's software license with Adobe, you have access to the Firefly web app and generative AI features inside apps like Photoshop and Illustrator as well as Adobe Stock.

More Software

- Generative AI Product Tracker (Ithaka S+R) - lists generative AI products that are either marketed specifically towards postsecondary faculty or students or appear to be actively in use by postsecondary faculty or students for teaching, learning, or research activities

- The Best AI Productivity Tools (Zapier)

- The Top AI Tools to Help You Study in College (ComputerScience.org)

- Using AI For Neurodiversity And Building Inclusive Tools (Pratik Joglekar, Smashing Magazine)

- Best AI Tools for Students (International University of Applied Sciences)

Productivity

- BeeDone Turns boring tasks into little games, offering rewards whenever you move forward. It keeps track of your habits, offers an AI assistant to guide you, and you can spin the Task Roulette if you feel like tackling a random one from your list. Free option available.

- goblin.tools A collection of small, simple, single-task tools, mostly designed to help neurodivergent people with tasks they find overwhelming or difficult. Free for everyone.

- Any.do An easy-to-manage to-do list that can help you organize personal tasks, family projects, and teams all in one place. Free tier available.

- Todoist A task manager that allows you to capture and organize tasks instantly, simplify your planning, and manage personal or team projects. Free tier available.

Calendar Management

- Reclaim AI calendar for work and life. Optimizes schedules for better productivity, collaboration, and work-life balance. Free "Lite" tier option.

- Clockwise Works across entire teams and companies to craft schedules based on preferences. Free tier available.

- Motion Automatically plan your day based on your tasks and priorities, focusing on project management. Free trial with tiered plans after trial ends.

See more scheduling assistants and comparison charts here.

Sources: The best AI productivity tools in 2024 Miguel Rebelo, Zapier Blog

Meetings

- Firefly Helps your team transcribe, summarize, search, and analyze voice conversations. Can transcribe meetings, tracking the conversation topics along the way. It has a bot called Fred that can handle summarize the meeting's contents, generating text, and searching through your history to meet your query. Free tier available.

- Krisp Maximizes the productivity of online meetings with its AI-powered Noise Cancellation, Transcriptions, Meeting Notes and Recording. Free tier available.

- Otter.ai Never take meeting notes again. Get transcripts, automated summaries, action items, and chat with Otter to get answers from your meetings. You can try Otter.ai for free, but paid versions allow for more minutes of recorded chats over a month.

Presentations & Websites

- Gamma Create unlimited presentations, websites, and more without coding. Free tier available.

- Slidesgo Generate presentations in minutes. Make changes to the presentation as needed. Free tier.

- Wix Website builder that allows you to design with a full suite of intuitive tools and powerful AI, manage your business, streamline your day-to-day with built-in business solutions, and expand your reach and monetize your website with integrated tools built for your success. Free with Wix branding and domain; from $17/month for the Light plan, including a custom domain for one year.

Email and Inbox Management

- SaneBox Uses A.I. to manage your email inbox, so you can focus on your most important work and get more done. Works with most inboxes. Free trial with tiered plans after trial ends.

- Mailbutler Email extension that adds useful features to your Apple Mail, Gmail, or Outlook inbox. Free trial with tiered plans after trial ends.

Learning & Note-Taking

- Socratic With help from teachers, Socratic brings you visual explanations of important concepts in a variety of subjects. Free.

- Notion An all-in-one workspace that allows students to organize and manage their tasks, notes, and projects. It combines the features of note-taking, task management, and project planning into a single platform. Free tier available.

- Evernote Use Evernote for note taking, project planning, and to find what you need, when you need it. Free tier available.

- Mem AI notes app that helps you locate, organize, and curate notes. Mem uses AI to tag and connect the notes you take, so you don't have to spend time organizing them.

Studying

- Anki An intelligent flashcard app that uses spaced repetition algorithms to help with memorization. Open source and free.

- ExamCram Convert notes to AI-Generated quizzes in minutes. Transform lecture slides, notes, and more into engaging quizzes for faster learning and better retention. Free to use.

Research

Note: Though this can help you summarize research more quickly, it is important to be cautious and read papers yourself if you plant to cite them or include them in your research

- Elicit Analyze research papers at superhuman speed. Automate time-consuming research tasks like summarizing papers, extracting data, and synthesizing your findings. . Free basic plan available.

- Scite Has a suite of products that help researchers develop their topics, find papers, and search citations in context (describing whether the article provides supporting or contrasting evidence). Free 7 day trial.

- Consensus Uses AI to help researchers find and synthesize answers to research questions, focusing on the scholarly authors' findings and claims in each paper. Free (20 searches/month); Paid version allows unlimited searching.

- Semantic Scholar Provides brief summaries ('TLDR's) of the main objectives and results of papers. Free.

See a comparison chart of AI tools for research here.

Citation Management

Note: Always double-check generated citations.

- Zotero Open-source citation management software that collects, manages, and cites research sources. Browser extension allows users to save citations with a single click. Free for IU students.

- Mendeley Citation management software with a focus on an online software with a matching desktop version, called Mendeley Reference Manager.

- Paperpile Manage your research library right in your browser, save time with a smart, intuitive interface, access your PDFs from anywhere, add citations and bibliographies to Google Docs. Free 30-day trial.

- ResearchRabbit A citation-based mapping tool that focuses on the relationships between research works. It uses visualizations to help researchers find similar papers and other researchers in their field.

Language Learning

- GPTionary "A next-generation thesaurus that empowers underprivileged communities, particularly non-native English speakers, to enhance their language abilities and open up doors to better education and job prospects." Search for words or phrases by describing them.

- Langotalk Get 24/7 language immersion with personalized AI chat-based tools. 7-day free trial.

- LanguaTalk Speak with human-like AI that’s available 24/7. Practice without pressure - you can make mistakes freely and get instant feedback. Free tier.

Chatbots have the potential to revolutionize our lives, make work more efficient, and free up time so that people can focus on other tasks. However, it is important to be very cautious when using chatbots. Not only are they newly-developed and continually evolving, but we have already seen bias in many other AI systems (see the "Centering Justice" tab for more. Before using an AI chatbot, make sure you understand the risk and be sure to use the AI Literacy Framework above to evaluate outputs. See below for articles on the risks of chatbots:

- When AI Gets It Wrong: Addressing AI Hallucinations and Bias (MIT Management)

- Three ways AI chatbots are a security disaster (Melissa Heikkilä, MIT Technology Review)

- Medical AI chatbots: are they safe to talk to patients? (Paul Webster, Nature Medicine)

- A faster, better way to prevent an AI chatbot from giving toxic responses (Adam Zewe, MIT News)

- Let’s Chat: Examining Top Risks Associated With Generative Artificial Intelligence Chatbots (Laura M. Cascella, MedPr Group)

Chatbots

Claude Built for work and trained to be safe, accurate, and secure. Claude can answer nuanced questions and create a variety of content. Trained by Anthropic using Constitutional AI. While Claude is fast and well-organized, it is not connected to the internet and does not automatically provide sources. Free tier available.

Perplexity A research chatbot that is good at providing sources (which it lists in an easily-accessible sidebar). Though Perplexity gives nuanced answers in an easy-to-follow list, it does tend to rely on Reddit posts as sources, which most people cannot cite for their projects. Free tier available.

ChatGPT Offers meaningful answers with a good amount of context on a variety of topics. While ChatGPT is good at most tasks like research and writing emails, it can be slow at times and it can be tedious to get ChatGPT to cite its sources. Developed by OpenAI and free to use.

InterviewBy.ai Practice job interview questions tailored to your job description. Get instant AI feedback and suggestions to improve your answers. Free plan includes 3 questions/month

Transcription

- Otter.ai Get transcripts, automated summaries, action items, and chat with Otter to get answers from your meetings, lectures, or other recorded materials. You can try Otter.ai for free, but paid versions allow for more minutes of recorded chats over a month.

Visuals and Photography

- Photoshop With generative AI in Photoshop you can create just about anything you can imagine using simple text prompts. Zip through dozens of ideas and generate new assets with Text to Image. Photoshop is free for IU community members.

- remove.bg Remove image background and replace it with a transparent background (PNG), white background, or get the cutout of a photo.

- Clipdrop by Jasper Remove backgrounds, people, or text from images. Free tier available.

AI Detectors

- Originality.ai AI Checker, plagiarism checker, and fact checker. You can get 50 credits by installing the free AI detection Chrome Extension to test Originality.ai’s detection capabilities. 1 credit can scan 100 words.

- Brandwell The AI Detector identifies ChatGPT, Gemini, Claude, and various other AI models. Tells you if something sounds like it is written by a human or if it sounds robotic. 7-day free trial.

AI Literacy

Though many people have grown up surrounded by AI technologies that have affected everything from traffic patterns to the products available at grocery stores, the recent release of ChatGPT brought AI to the forefront of our lives. The increased accessibility of AI bring with it a need for AI literacy. In this context, literacy does not simply refer to the ability to use AI technologies but to the combination of knowledge and skills that allow users to critically understand and evaluate AI tools in an increasingly digital world. In our daily lives, we implement information, media, financial, and health literacy when performing all kinds of tasks. When practicing AI literacy, one might ask questions like: How does this technology work? What kind of data was this system trained on? What biases are present in this technology? How does this impact my world and the world around me?

Source: AI Literacy, Explained (Alyson Klein; EducationWeek, May 10, 2023)

Whether we realize it or not, we utilize different literacies every day. For example, when we read the news we might use an information literacy framework to determine whether or not we can trust the media which we encounter. We can ask questions about who created or funded an article, about why the message of the piece is being sent, and about what kind of research went into the piece.

Similarly, we can apply an AI literacy framework when utilizing AI-enabled technologies or engaging with the outputs of such systems. Various scholars and institutions have developed AI literacy frameworks to encourage users to think critically about their use of AI tools. These frameworks propose practices and benchmarks that define how users can understand and evaluate AI-enabled tools as well as how educators can support AI literacy development.

Below we give a basic overview of just a few of these AI literacy frameworks. In doing so, we aim to highlight how this one concept can be applied differently: while the goal of AI literacy is largely consistent, there is currently no single unified definition or assessment framework for it. Of course, we encourage you to explore more deeply the research and documentation of each framework to gather a more complete understanding of the principles and practices they propose.

Literature review by Ng et al. (2021)

Ng et al. (2021) conducted a literature review on AI literacy, synthesizing existing research to create a consolidated definition of AI literacy and to shed light on associated teaching and ethical concerns. The researchers identified four overarching aspects of AI literacy from the literature:

- Know & understand AI - Know the basic functions of AI and how to use AI applications in everyday life ethically.

- Apply AI - Applying AI knowledge, concepts and applications in different scenarios.

- Evaluate & create AI - Higher-order thinking skills (e.g., evaluate, appraise, predict, design) with AI applications.

- AI ethics - Human-centered considerations (e.g., fairness, accountability, transparency, ethics)

By establishing this foundational understanding of AI Literacy, the authors lay the “groundwork for future research such as competency development and assessment criteria on AI literacy.” Indeed, since the study’s publication multiple organizations and academic institutions have developed their own AI literacy models and curricula. For more information, consult the original study, cited below.

Source: Ng, D. T. K., Leung, J. K. L., Chu, S. K. W., & Qiao, M. S. (2021). “Conceptualizing AI literacy: An exploratory review.” Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 2, 100041. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2021.100041

AI Across the Curriculum: University of Florida 2024-2029 Quality Enhancement Plan

With its extensive computational infrastructure, the University of Florida is positioned at the forefront of AI research and development. In an effort to utilize these resources and to advance the university’s mission, a task force made up of students, faculty, staff, and administrators developed the AI Across the Curriculum program.

This five-year quality enhancement plan is “designed to provide students with the resources and skills to become successful digital citizens and global collaborators, acquire basic awareness and general knowledge of AI, have the opportunity to apply and use AI in relevant, discipline-specific ways, and develop foundational expertise in AI.”

Their AI literacy framework is largely based on the categories identified by Ng et al. (2021). In order to assess student learning and performance across these domains of AI literacy, the plan includes quantitative and qualitative assessment protocols, including a rubric of six student learning outcomes:

- Identify, describe, and/or explain the components, requirements, and/or characteristics of AI.

- Identify, describe, define and/or explain applications of AI in multiple domains.

- Select and/or utilize AI tools and techniques appropriate to a specific context and application.

- Develop, apply, and/or evaluate contextually appropriate ethical frameworks to use across all aspects of AI.

- Assess the context-specific value or quality of AI tools and applications.

- Conceptualize and/or develop tools, hardware, data, and/or algorithms utilized in AI solutions.

Source: Migliaccio, K., Southworth, J., Reed, D., Miller, D., Leite, M. C., & Donovan, M. (2024). AI Across the Curriculum: University of Florida 2024-2029 Quality Enhancement Plan. University of Florida. https://ai.ufl.edu/media/aiufledu/resources/25_01.08_UF-QEP_AI-Across-the-Curriculum.pdf

The Digital Promise Framework (June 2024)

This framework “consists of three interconnected Modes of Engagement: Understand, Evaluate, and Use. The framework emphasizes that understanding and evaluating AI are critical to making informed decisions about if and how to use AI in learning environments.” Expanding on these overarching goals, the authors also propose six actionable AI-literacy practices, which include:

- Algorithmic Thinking, Abstraction & Decomposition - Develop and/or use a computer’s ability to recognize data and create a prediction or perform an action based on both the situation and stored information without explicit human guidance.

- Data Analysis & Inference - Consider the context of datasets, data visualizations, and data collection with criticality. Assess quality of training data for AI tools and leverage AI models and methods to collect, analyze, and visualize data.

- Data Privacy & Security - Develop awareness of data privacy and security while fostering ownership and agency of how to protect data in AI-enabled systems. This includes the privacy and security of personal data collected by an AI system or tool and how that data is used.

- Digital Communication & Expression - Understand how AI Systems create synthetic content, evaluate synthetic AI creations, and consider ethical responsibilities when consuming, creating, and sharing AI-enabled products.

- Ethics & Impact - Examine the outputs of algorithms and question the biases inherent in the AI systems and tools being used. Consider the benefits and harms of AI tools to the environment, people, or society. Importantly, it includes considering how datasets, including their accessibility and representation, reproduce bias in our society.

- Information & Mis/Disinformation - Determine credibility of AI system outputs in digital landscapes. This includes evaluating datasets and AI products/outputs for false, inaccurate or misleading information.

For a more detailed and comprehensive view of this framework, please refer to Digital Promise’s website.

Source: Mills, K., Ruiz, P., Lee, K., Coenraad, M., Fusco, J., Roschelle, J., & Weisgrau, J. (2024, May). AI Literacy: A Framework to Understand, Evaluate, and Use Emerging Technology. https://doi.org/10.51388/20.500.12265/218

The Barnard College Framework (June 2024)

Recognizing the ever-evolving development of AI-tools and their impact on the higher education environment, academic and technologies teams at Barnard College developed an AI literacy framework to provide “a structure for learning to use AI, including explanations of key AI concepts and questions to consider when using AI.” The framework consists of a four-part pyramid structure that breaks down AI literacy into four levels:

- Understand AI

- Use and Apply AI

- Analyze and Evaluate AI

- Create AI

Each level has its own set of core competencies, key concepts, and reflection questions. For a more detailed and comprehensive view of this framework, read about it here.

Source: Hibbert, M., Altman, E., Shippen, T., & Wright, M. (2024) “A Framework for AI Literacy.” EDUCAUSE Review. https://er.educause.edu/articles/2024/6/a-framework-for-ai-literacy

The ROBOT Test

Similar to an AI Literacy framework, the ROBOT test, developed by librarians at McGill University (Amanda Wheatley and Sandy Hervieux) offers a helpful mnemonic for evaluating AI systems and outputs. "Being AI Literate does not mean you need to understand the advanced mechanics of AI. It means that you are actively learning about the technologies involved and that you critically approach any texts you read that concern AI, especially news articles."

Reliability Objective Bias Ownership Type

| Reliability |

|

| Objective |

|

| Bias |

|

| Owner |

|

| Type |

|

From the personal computer to the internet, information institutions have a long history of adapting to emerging technologies. The development of AI technologies has proven to be another technological turning point, one to which all industries – not just libraries, museums, and archives – must adapt.

Just as AI literacy frameworks have been implemented to help individuals better understand and utilize AI-enabled tools, library professionals have developed AI decision-making frameworks to aid libraries, archives, and museums in adopting this new technology at the institutional level. Below we highlight a few of these frameworks. To get even more involved, consider joining a professional committee or discussion group on AI implementation, such as the Association of College and Research Libraries' Artificial Intelligence Discussion Group.

LC Labs AI Planning Framework

Professionals at the Library of Congress have identified machine learning “as a potential way to provide more metadata and connections between collection items and users.” Recognizing that the impact of AI use in library operations is an ongoing subject of study, they developed “a planning framework to support the responsible exploration and potential adoption of AI at the Library.” Broadly speaking, the framework includes three planning phases:

- Understand

- Experiment

- Implement

Moreover, each phase supports the evaluation of three elements of machine learning:

- Data

- Models

- People

They have also developed supplementary materials – including worksheets, questionnaires, and workshops – “to engage stakeholders and staff and identify priorities for future AI enhancements and services.”

The folks at the Library of Congress recognize that no single institution can tackle the task of AI implementation alone. In order to successfully adapt to the challenges this new technology poses, the authors emphasize that professionals across the library sector must co-develop, communicate, and share information regarding requirements, policy, governance, infrastructure and costs.

To read more about this planning framework and how the Library of Congress has applied it, check out this post on the Library of Congress blog!

Practical Ethics for Librarians: Navigating Generative AI Thoughtfully

Dr. Leo. S. Lo offers a framework for approaching AI integration in libraries through the lens of practical ethics. He encourages librarians to apply various ethical theories to questions surrounding AI:

- Deontological ethics - Some actions are inherently right or wrong, regardless of consequences.

- Consequentialist ethics - The morally right action is the one that maximizes the best overall result or minimizes harm.

- Value ethics - Focuses on the moral qualities that should be expressed in decisions.

All of these ethical frameworks have their own pros and cons, and they certainly cannot give us final definitive answers to ethical dilemmas. However, they offer a structured approach to making decisions in accordance with library values, user rights, and professional ethics. Lo provides a seven-step framework with which libraries can make institutional decisions regarding AI:

- Identify the Ethical Dilemma

- Gather Information

- Apply the AI Ethics Checklist

- Evaluate Options & Trade-Offs

- Make a Decision & Document It

- Implement & Monitor

- Follow the AI Ethics Review Cycle

To read more about this framework and its applications, check out the slide deck for Dr. Lo’s presentation.

Viewfinder: A Toolkit for Values-driven AI in Libraries & Archives

Librarians at Montana State University have developed “tools and strategies that support responsible use of AI in the field” through an IMLS-funded project titled, Responsible AI in Libraries and Archives. One result of this research initiative was Viewfinder, a toolkit “designed to facilitate ethical reflection about AI in libraries and archives from different stakeholder perspectives.”

This toolkit provides a structure for a workshop for organizational AI-implementation project teams. The toolkit guides participants in considering which ethical and professional values might matter to different stakeholders in different scenarios involving AI-enabled tools. This framework encourages participants to reflect on the many factors at play in implementing AI tools at the organizational level and to gather a more holistic understanding of a particular implementation initiative.

Source: Mannheimer, S., Clark, J. A., Young, S. W. H., Shorish, Y., Kettler, H. S., Rossmann, D., Bond, N., & Sheehey, B. (2023). Responsible AI in Libraries. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/RE2X7

Articles

-

AI Literacy, Explained (Alyson Klein, EducationWeek)AI literacy is something that every student needs exposure to—not just those who are planning on a career in computer science, experts argue.

-

Conceptualizing AI literacy: An exploratory review (Ng, D.T.K., Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence)An exploratory review was conducted to conceptualize the newly emerging concept “AI literacy” to define, teach and evaluate AI literacy. This review proposed four aspects (i.e., know and understand, use, evaluate and ethical issues) for fostering AI literacy based on the adaptation of classic literacies.

Books

For more books, see the following subject headings in IUCAT:

-

Computational Thinking Education in K-12: Artificial intelligence literacy and physical computing by

ISBN: 9780262543477Publication Date: 2022-05-03A guide to computational thinking education, with a focus on artificial intelligence literacy and the integration of computing and physical objects. Computing has become an essential part of today's primary and secondary school curricula. In recent years, K-12 computer education has shifted from computer science itself to the broader perspective of computational thinking (CT), which is less about technology than a way of thinking and solving problems-"a fundamental skill for everyone, not just computer scientists," in the words of Jeanette Wing, author of a foundational article on CT. This volume introduces a variety of approaches to CT in K-12 education, offering a wide range of international perspectives that focus on artificial intelligence (AI) literacy and the integration of computing and physical objects. -

AI Literacy in K-16 Classrooms by

ISBN: 9783031188794Publication Date: 2022-12-08Artificial Intelligence is at the top of the agenda for education leaders, scientists, technologists and policy makers in educating the next generation across the globe. Beyond applying AI in daily life applications and educational tools, understanding how to learn and teach AI is increasingly important. Despite these emerging technology breakthroughs, AI learning is still new to educators especially to K-16 teachers. There is a lack of evidence-based studies that inform them about AI learning, including design principles for building a set of curriculum content, and pedagogical approaches as well as technological tools. Teaching AI concepts and techniques from programming languages and developmentally appropriate learning tools (e.g., robotics, serious games, software, intelligent agents) across different education levels emerged in recent years. The primary purpose of this book is to respond to the need to conceptualize the emerging term "AI literacy" and investigate how to teach and learn AI in K-16 education settings. -

School Children and the Challenge of Managing AI Technologies: Fostering a critical relationship through aesthetic experiences by

ISBN: 9781032694276Publication Date: 2024-06-01This edited volume recognises the need to cultivate a critical and acute understanding of AI technologies amongst primary and elementary school children, enabling them to meet the challenge of a human- and ethically oriented management of AI technologies. Focusing on school settings from both the national and international level to form comparative case studies, chapters present a robust conceptual and foundational framework within a global context as the idea of AI and our relationship to it advances apace. Providing an innovative perspective in promoting the importance of a critical, creative and ethical orientation based on aesthetic experiences, the book focuses on development in areas like visual arts, literature, environmental education, robotics, photography and screen education, movement and play. -

Developing middle schoolers' artificial intelligence literacy through project-based learning: Investigating cognitive & affective dimensions of learning about AI

by

ISBN: 9798379988272Publication Date: 2023Indiana University; Ann Arbor : ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. This study investigated middle school students' Artificial Intelligence (AI) literacy, focusing on cognitive and affective dimensions with regard to learning about AI.

Developing middle schoolers' artificial intelligence literacy through project-based learning: Investigating cognitive & affective dimensions of learning about AI

by

ISBN: 9798379988272Publication Date: 2023Indiana University; Ann Arbor : ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. This study investigated middle school students' Artificial Intelligence (AI) literacy, focusing on cognitive and affective dimensions with regard to learning about AI.

Citation

Since the results of an AI chatbot are not retrievable by other users, it is important to provide sufficient context when using AI-generated content in your research. For example, many style guides recommend discussing how you have used AI in the methods section of your paper or describing how you used said tool in your introduction or footnotes. In your text, you can provide the prompt you used and then any portion of the relevant text that was generated in response.

MLA suggests that you:

- cite a generative AI tool whenever you paraphrase, quote, or incorporate into your own work any content (whether text, image, data, or other) that was created by it

- acknowledge all functional uses of the tool (like editing your prose or translating words) in a note, your text, or another suitable location

- take care to vet the secondary sources it cites (see example 5 below for more details)

According to Chicago, "you do need to credit ChatGPT and similar tools whenever you use the text that they generate in your own work. But for most types of writing, you can simply acknowledge the AI tool in your text (e.g., “The following recipe for pizza dough was generated by ChatGPT”)."

Citing AI-generated content will look different depending on the style you are using. We have provided guidelines for APA, MLA, Chicago, and IEEE in the next tab.

APA

Template: Author. (Date).Title (Month Day version) [Additional Descriptions ]. Source

Author: The author of the model.

Date: The year of the version.

Title: The name of the model.The version number is included after the title in parentheses.

Bracketed text: References for additional descriptions

Source: When the publisher and author names are identical, omit the publisher name in the source element of the reference and proceed directly to the URL.

Example

Quoted in Your Prose

When prompted with “Is the left brain right brain divide real or a metaphor?” the ChatGPT-generated text indicated that although the two brain hemispheres are somewhat specialized, “the notation that people can be characterized as ‘left-brained’ or ‘right-brained’ is considered to be an oversimplification and a popular myth” (OpenAI, 2023).

Reference Entry

OpenAI. (2023). ChatGPT (Mar 14 version) [Large language model]. https://chat.openai.com/chat

MLA

Author: We do not recommend treating the AI tool as an author. This recommendation follows the policies developed by various publishers, including the MLA’s journal PMLA.

Title of Source: Describe what was generated by the AI tool. This may involve including information about the prompt in the Title of Source element if you have not done so in the text.

Title of Container: Use the Title of Container element to name the AI tool (e.g., ChatGPT).

Version: Name the version of the AI tool as specifically as possible. For example, the examples in this post were developed using ChatGPT 3.5, which assigns a specific date to the version, so the Version element shows this version date.

Publisher: Name the company that made the tool.

Date: Give the date the content was generated.

Location: Give the general URL for the tool

Example 1: Paraphrasing Text

Paraphrased in Your Prose

While the green light in The Great Gatsby might be said to chiefly symbolize four main things: optimism, the unattainability of the American dream, greed, and covetousness (“Describe the symbolism”), arguably the most important—the one that ties all four themes together—is greed.

Works-Cited-List Entry

“Describe the symbolism of the green light in the book The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald” prompt. ChatGPT, 13 Feb. version, OpenAI, 8 Mar. 2023, chat.openai.com/chat.

Example 2: Quoting Text

Quoted in Your Prose

When asked to describe the symbolism of the green light in The Great Gatsby, ChatGPT provided a summary about optimism, the unattainability of the American dream, greed, and covetousness. However, when further prompted to cite the source on which that summary was based, it noted that it lacked “the ability to conduct research or cite sources independently” but that it could “provide a list of scholarly sources related to the symbolism of the green light in The Great Gatsby” (“In 200 words”).

Works-Cited-List Entry

“In 200 words, describe the symbolism of the green light in The Great Gatsby” follow-up prompt to list sources. ChatGPT, 13 Feb. version, OpenAI, 9 Mar. 2023, chat.openai.com/chat.

For examples of citing creative visual works, quoting creative textual works, and citing secondary sources used by an AI tool, see the MLA Style Center Generative AI page.

Chicago

According to Chicago, "you do need to credit ChatGPT and similar tools whenever you use the text that they generate in your own work. But for most types of writing, you can simply acknowledge the AI tool in your text (e.g., “The following recipe for pizza dough was generated by ChatGPT”)."

To sum things up, you must credit ChatGPT when you reproduce its words within your own work, but unless you include a publicly available URL, that information should be put in the text or in a note—not in a bibliography or reference list. Other AI-generated text can be cited similarly.

If you do need a citation:

Author: The name of the tool that your are using (such as ChatGPT)

Publisher: Name the company that made the tool (such as OpenAI)

Date: Give the date the content was generated.

Location: Give the general URL for the tool. Because readers can’t necessarily get to the cited content (see below), that URL isn’t an essential element of the citation.

A numbered footnote or endnote might look like this:

1. Text generated by ChatGPT, OpenAI, March 7, 2023, https://chat.openai.com/chat.

If you’re using author-date instead of notes, any information not in the text would be placed in a parenthetical text reference:

“(ChatGPT, March 7, 2023).”

IEEE

According to the IEEE guide, "the use of content generated by artificial intelligence (AI) in an article (including but not limited to text, figures, images, and code) shall be disclosed in the acknowledgments section of any article submitted to an IEEE publication. The AI system used shall be identified, and specific sections of the article that use AI-generated content shall be identified and accompanied by a brief explanation regarding the level at which the AI system was used to generate the content. The use of AI systems for editing and grammar enhancement is common practice and, as such, is generally outside the intent of the above policy. In this case, disclosure as noted above is recommended."

Sources: How to cite ChatGPT (Timothy McAdoo, APA Style Blog); Ask The MLA: How do I cite generative AI in MLA style? (MLA Style Center); How to Cite AI-Generated Content (Purdue University); Citation, Documentation of Sources: Artificial Intelligence (The Chicago Manual of Style Online); Submission and Peer Review Policies: Guidelines for Artificial Intelligence (AI)-Generated Text (IEEE Author Center)

Harker, J. (2023, March). Science journals set new authorship guidelines for AI-generated text. National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. https://factor.niehs.nih.gov/2023/3/feature/2-artificial-intelligence-ethics

Shope, M. L. (2023). Best Practices for Disclosure and Citation When Using Artificial Intelligence Tools. GLJ Online (Georgetown Law Journal Online), 112, 1–22.

APA publishes high-quality research that undergoes a rigorous and ethical peer review process. Journal policies for authors are provided for transparency and clarity, including ethical expectations, AI guidance, and reuse.

COPE (Committee on Publication Ethics) Position Statement on Authorship and AI Tools

The use of artificial intelligence (AI) tools such as ChatGPT or Large Language Models in research publications is expanding rapidly. COPE joins organisations, such as WAME and the JAMA Network among others, to state that AI tools cannot be listed as an author of a paper. AI tools cannot meet the requirements for authorship as they cannot take responsibility for the submitted work. As non-legal entities, they cannot assert the presence or absence of conflicts of interest nor manage copyright and license agreements.

AI and Education

AI has many applications at all levels of education. Though we may know AI best for the way it has reshaped student learning (through the proliferation of generative AI technologies that can create text, code, and other types of content), AI is also utilized by teachers and administrators. Predictive AI tools can analyze patterns in student data to forecast outcomes such as graduation rates and student learning milestones. These insights allow educators to intervene proactively but require careful evaluation for potential bias. See some more uses of AI in education below:

Chart: Examples of AI Applications in Education (Digital Promise).

AI also has many potential benefits when implemented in an educational setting. Of course, there are many risks as well:

Graphic: Potential risks and benefits of AI in education (TeachAI).

In this box, we have selected frameworks, toolkits, books, and articles that will help teachers and students implement and utilize AI in their classrooms.

-

Artificial Intelligence Collection (EducationWeek)Find out how artificial intelligence could change education, inside the classroom and out

-

SAFE Benchmarks FrameworkThe framework was built starting in 2021 and brings together more than 24 global AI safety, trust and market frameworks. Frameworks and benchmarks are essential to innovation as a means of targeted guidance, focusing disparate efforts towards shared language, objectives, and outcomes and ensuring the development of appropriate guidelines and guardrails for use. By working together through the Framework, EDSAFE aims to accomplish two things: achieve equitable outcomes for students and improve working conditions for teachers.

-

An AI Bill of Rights for Educators (EngageAI Institute)As the development and deployment of artificial intelligence (AI), including generative AI applications,

has been accelerating in recent years, many educators have expressed their desire to implement these

tools in support of their students. To support the safe and ethical implementation of these powerful

tools in educational settings, we outline a set of six rights for educators. -

Responsible AI and Tech Justice: A Guide for K-12 EducationIncludes articles, case studies, lesson plans, and additional resources centered around six core components of understanding and ethically utilizing AI-enables systems.

-

Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Teaching and Learning (U.S. Department of Education)This report addresses the need for sharing knowledge and developing policies for Artificial Intelligence, a rapidly advancing class of foundational capabilities which are increasingly embedded in all types of educational technology systems. This report considers “educational technology” (edtech) to include both (a) technologies specifically designed for educational use, as well as (b) general technologies that are widely used in educational settings. Recommendations in this report seek to engage teachers, educational leaders, policy makers, researchers, and educational technology innovators and providers as they work together on pressing policy issues that arise as Artificial Intelligence (AI) is used in education.

-

Shaping the Future of Learning: The Role of AI in Education 4.0This report explores the potential for artificial intelligence to benefit educators, students and teachers. Case studies show how AI can personalize learning experiences, streamline administrative tasks, and integrate into curricula.

For more books, see the following subject headings in IUCAT:

- "Artificial intelligence--Study and teaching"

- "Artificial intelligence--Educational applications"

- "Education Higher--Effect of technological innovations on"

AI Educational Ethics and Futures

-

The Ethics of Artificial Intelligence in Education by

ISBN: 9780367349721Publication Date: 2022-08-11The Ethics of Artificial Intelligence in Education identifies and confronts key ethical issues generated over years of AI research, development, and deployment in learning contexts. Adaptive, automated, and data-driven education systems are increasingly being implemented in universities, schools, and corporate training worldwide, but the ethical consequences of engaging with these technologies remain unexplored. Featuring expert perspectives from inside and outside the AIED scholarly community, this book provides AI researchers, learning scientists, educational technologists, and others with questions, frameworks, guidelines, policies, and regulations to ensure the positive impact of artificial intelligence in learning. -

Artificial Intelligence and Learning Futures: Critical narraves of technology and imagination tiin higher education by

ISBN: 9781003266563Publication Date: 2022-11-30Artificial Intelligence and Learning Futures explores the implications of artificial intelligence's adoption in higher education and the challenges to building sustainable instead of dystopic schooling. As AI becomes integral to both pedagogy and profitability in today's colleges and universities, a critical discourse on these systems and algorithms is urgently needed to push back against their potential to enable surveillance, control, and oppression. This book examines the development, risks, and opportunities inherent to AI in education and curriculum design, the problematic ideological assumptions of intelligence and technology, and the evidence base and ethical imagination required to responsibly implement these learning technologies in a way that ensures quality and sustainability. -

Artificial Intelligence in the Capitalist University: Academic labour, commodification, and value by

ISBN: 9780367533779Publication Date: 2021-11-05Using Marxist critique, this book explores manifestations of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Higher Education and demonstrates how it contributes to the functioning and existence of the capitalist university. Challenging the idea that AI is a break from previous capitalist technologies, the book offers nuanced examination of the impacts of AI on the control and regulation of academic work and labour, on digital learning and remote teaching, and on the value of learning and knowledge. Applying a Marxist perspective, Preston argues that commodity fetishism, surveillance, and increasing productivity ushered in by the growth of AI, further alienates and exploits academic labour and commodifies learning and research. Offering an impactful and timely analysis, this book provides a critical engagement and application of key Marxist concepts in the study of AI's role in Higher Education. -

Augmented Education in the Global Age: Artificial intelligence and the future of learning and work by

ISBN: 9781032122939Publication Date: 2023-03-23Augmented Education in the Global Age: Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Learning and Work is an edited collection that explores the social impact of Artificial Intelligence over the coming decades, specifically how this emerging technology will transform and disrupt our contemporary institutions. Chapters in this book discuss the history of technological revolutions and consider the anxieties and social challenges of lost occupations, as well as the evolution of new industries overlapping robotics, biotechnology, space exploration, and clean energy. Ultimately the book discusses policy and planning for an augmented future, arguing that work and learning are undergoing a metamorphosis around creativity and innovation amid a new global era and the race against automating technologies. -

Algorithmic Rights and Protections for Children by

ISBN: 9780262545488Publication Date: 2023-06-27Essays on the challenges and risks of designing algorithms and platforms for children, with an emphasis on algorithmic justice, learning, and equity. One in three Internet users worldwide is a child, and what children see and experience online is increasingly shaped by algorithms. Though children's rights and protections are at the center of debates on digital privacy, safety, and Internet governance, the dominant online platforms have not been constructed with the needs and interests of children in mind. This book includes essays reporting original research on educational programs in AI relational robots and Scratch programming, on children's views on digital privacy and artificial intelligence, and on discourses around educational technologies. Their essays also build on recent research examining how social media, digital games, and learning technologies reflect and reinforce unequal childhoods.

Teaching and Working with AI

-

Teaching with AI by

ISBN: 9781421449227Publication Date: 2024-04-30Artificial Intelligence (AI) is revolutionizing the way we learn, work, and think. Its integration into classrooms and workplaces is already underway, impacting and challenging ideas about creativity, authorship, and education. In this groundbreaking and practical guide, teachers will discover how to harness and manage AI as a powerful teaching tool. José Antonio Bowen and C. Edward Watson present emerging and powerful research on the seismic changes AI is already creating in schools and the workplace, providing invaluable insights into what AI can accomplish in the classroom and beyond. From interactive learning techniques to advanced assignment and assessment strategies, this comprehensive guide offers practical suggestions for integrating AI effectively into teaching and learning environments. Bowen and Watson tackle crucial questions related to academic integrity, cheating, and other emerging issues. In the age of AI, critical thinking skills, information literacy, and a liberal arts education are more important than ever. This book serves as a compass, guiding educators through the uncharted territory of AI-powered education and the future of teaching and learning. -

Using Generative AI Effectively in Higher Education: Sustainable and ethical practices for learning, teaching and assessment by

ISBN: 9781032773988Publication Date: 2024-06-14Using Generative AI Effectively in Higher Education explores how higher education providers can realise their role and responsibility in harnessing the power of generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) ethically and sustainably. This rich collection of established and evaluated practices from across global higher education offers a practical guide to leading an agile institutional response to emerging technologies, building critical digital literacy across an entire institution, and embedding the ethical and sustainable use of GenAI in teaching, learning, and assessment. It provides an evidence-based resource for any kind of higher education (HE) provider (modern, college-based, and research-focused) looking for inspiration and approaches which can build GenAI capability and includes chapters on the development of cross-institutional strategy, policies and processes, pedagogic practices, and critical-digital literacy. -

Embracing Chatbots in Higher Education: The Use of Artificial Intelligence in Teaching, Administration, and Scholarship by

ISBN: 9781032685977Publication Date: 2024This book explores the integration of AI-powered chatbots such as ChatGPT into higher education for instructional and communication purposes. The author emphasizes the responsibility of higher education institutions to equip students with advanced skills for writing with AI assistance, and prepare them for an increasingly AI-driven world. Offering numerous practical tips, the book demonstrates how universities can increase student success, and stem the rising cost of higher education by employing AI tools. -

Computational Thinking Education in K-12: Artificial intelligence literacy and physical computing by

ISBN: 9780262543477Publication Date: 2022-05-03A guide to computational thinking education, with a focus on artificial intelligence literacy and the integration of computing and physical objects. Computing has become an essential part of today's primary and secondary school curricula. In recent years, K-12 computer education has shifted from computer science itself to the broader perspective of computational thinking (CT), which is less about technology than a way of thinking and solving problems-"a fundamental skill for everyone, not just computer scientists," in the words of Jeanette Wing, author of a foundational article on CT. This volume introduces a variety of approaches to CT in K-12 education, offering a wide range of international perspectives that focus on artificial intelligence (AI) literacy and the integration of computing and physical objects. -

School Children and the Challenge of Managing AI Technologies: Fostering a critical relationship through aesthetic experiences by

ISBN: 9781032694276Publication Date: 2024-06-01This edited volume recognises the need to cultivate a critical and acute understanding of AI technologies amongst primary and elementary school children, enabling them to meet the challenge of a human- and ethically oriented management of AI technologies. Focusing on school settings from both the national and international level to form comparative case studies, chapters present a robust conceptual and foundational framework within a global context as the idea of AI and our relationship to it advances apace. Providing an innovative perspective in promoting the importance of a critical, creative and ethical orientation based on aesthetic experiences, the book focuses on development in areas like visual arts, literature, environmental education, robotics, photography and screen education, movement and play. -

Utilizing AI Tools in Academic Research Writing by

ISBN: 9798369317983Publication Date: 2024-05-31Those entrenched in academia often have daunting processes of formulating research questions, data collection, analysis, and scholarly paper composition. Artificial intelligence (AI) emerges as an invaluable ally, simplifying these processes and elevating the quality of scholarly output. Where the pursuit of knowledge meets the cutting edge of technology, Utilizing AI Tools in Academic Research Writing unfolds a transformative journey through the symbiotic relationship between AI and academic inquiry. This book extends beyond theoretical discussions, delving into practical dimensions of AI integration, demonstrating how it facilitates topic identification, refines research design, empowers data analysis, and enriches literature reviews. Ethical considerations in AI-integrated research take center stage, emphasizing responsible and transparent practices. Real-world case studies and examples across diverse academic disciplines provide tangible illustrations of AI's transformative impact, making this guide a practical companion for all stages of academic inquiry.

-

AI Is Transforming Humanitites Research (Moira Donovan, MIT Technology Review)Historians are using neural networks to draw new connections in the analysis of history.

-

The AI-Powered Nonprofits Reimagining Education (Kevin Barenblat & Brooke James, Stanford Social Innovation Review)AI is being used in exciting ways to bridge educational divides, and AI-powered nonprofits are creating a roadmap for what the future of education may hold.

-

EDUCAUSE QuickPoll Results: Adopting and Adapting to Generative AI in Higher Ed Tech (Mark McCormack)As more higher education stakeholders discover and use generative AI, intentional staffing and governance will ensure that institutions adopt these technologies effectively and appropriately.

-

Artificial Intelligence In Education: Teachers’ Opinions On AI In The Classroom (Ilana Hamilton, Forbes)In October 2023, Forbes Advisor surveyed 500 practicing educators from around the U.S. about their experiences with AI in the classroom. With respondents representing teachers at all career stages, the results reveal a snapshot of how artificial intelligence is impacting education.

Centering Justice