Introduction

The amount of information we have access to is overwhelming, and, consequently, determining whether or not that information is reliable isn't always straightforward. The resources here have been curated to help you evaluate sources as you move through complex information ecosystems (especially online). The usefulness of a source and how “good” or “bad” it is will be determined by your needs and its relevance to your question. Sometimes, you will need scholarly articles that have been peer-reviewed by experts in the field. Other times, you might need first hand accounts from people with lived experiences in your topic of interest. Remember, any kind of resource can be appropriate and useful for your research, as long as you understand the particularities of each source type, as well as their perspectives and biases.

Below is a helpful video from Portland Community College on evaluating sources and finding quality research that will be useful for your assignment:

Video: Evaluating Sources to Find Quality Research. PCC Library (2016).

See below for additional resources on understanding and evaluating sources:

- 33 Problems With Media in One ChartDespite all the benefits we receive when information flows freely, there are a number of broken systems and negative externalities as well. Acknowledging these shortcomings is the first step to solving them.

- Know Your Sources: A Guide to Understanding Sources from Portland Community College Library

When doing research you will come across a lot of information from different types of sources. How do you decide which source to use? From tweets to newspaper articles, this tool provides a brief description of each and breaks down 6 factors of what to consider when selecting a source.

When doing research you will come across a lot of information from different types of sources. How do you decide which source to use? From tweets to newspaper articles, this tool provides a brief description of each and breaks down 6 factors of what to consider when selecting a source.

Peer-Reviewed Sources

Peer Review

The goal of peer-review in academic publishing is to assess the quality of articles submitted for publication in a scholarly journal. Peer-review is exactly what it sounds like—articles must undergo a process of review by scholars in the field before they can be published in a peer-reviewed, academic journal. Here is an outline of the peer-review process:

- An author submits their article to a journal editor who forwards it to experts in the field. Because the reviewers specialize in the same field as the author, they are considered the author’s peers (hence, “peer review”).

- The reviewers carefully evaluate the submitted manuscript, checking it for accuracy and assessing the validity of the research methodology and procedures.

- If appropriate, they suggest revisions. If they find the article lacking in scholarly validity and rigor, they reject it.

- Because a peer-reviewed journal will not publish articles that fail to meet the standards established for a given discipline, peer-reviewed articles that are accepted for publication should exemplify the best research practices in a field (to learn more about peer review practices in the sciences, read this article from Harvard University.

Some databases (such as OneSearch@IU) allow you to filter results by peer-reviewed articles. It good practice to double check the journals from which the articles come to make sure that it is peer-reviewed (if this is what you are looking for). You can do this by googling the name of the journal. You can also refer to the following image when trying to determine if an article is peer-reviewed:

Image: Evaluating Information Sources: What Is A Peer-Reviewed Article? Lloyd Sealy Library, John Jay College of Criminal Justice (2019).

A Caveat About Peer Review

It is important to note that peer review is not equivalent to objectivity. Bias and subjectivity can show up in a number of ways, both before and during any process of peer or editorial review. The peer review process (as well as other scholarly mechanisms) also privileges certain ways of thinking, communicating, and knowing, and not all thinkers or communities have access to (or choose to take part in) this system. While peer review is an integral evaluative process within many fields, and is one pathway through which knowledge can be created and shared, we suggest an expansive framework for finding, using, and evaluating sources, and for students and scholars to consider information sources beyond what makes it into the scholarly conversation through peer review when possible and appropriate.

Types of Sources

Scholarly Sources

Scholarly sources are intended for academic use—often, these are often the peer-reviewed articles we discussed above. They utilize a specialized vocabulary and extensive citations. Scholarly sources help answer the "so what?" questions and make connections between variables (or issues). Scholarly sources:

- are published by academic institutions or scholarly platforms.

- are written by and for faculty, researchers, or other experts (including students) in a field.

- use scholarly, technical language.

- include a full bibliography of sources cited in the article.

- have minimal ads or other promotional material, usually for scholarly products (e.g., books) or field-related products.

Image: Academic Journals, Raising Your Scholarly Profile. Duquesne University (2023).

Additional Resources: Source Types

To learn more about scholarly, popular, and trade sources, explore the links and video below:

- Evaluating Sources: Scholarly, Popular, and Trade (Loyola Marymount University)

- Research Foundations: Popular, Scholarly, & Trade Publications (Seminole State College)

Video: Scholarly vs. Popular Periodicals. Vanderbilt University (2017).

Popular Sources

Popular sources are intended for the general public and are typically written to entertain, inform, and/or persuade. Popular sources help you answer "who, what, where, and when" questions and can range from research-oriented to propaganda-focused. Popular sources:

- are published by magazines, newspapers, websites, blogs, and government agencies.

- are written by anyone (often journalists, freelancers, sometimes experts) for the general public.

- use familiar, non-technical language.

- rarely include sources, may offer links within publication or to similarly-focused sources.

- have ads for a variety of different products.

Image: Research Process: A Step-by-Step Approach: Find Information Sources: Popular vs. Scholarly. Nash Library and Student Learning Commons, Gannon University.

How do I access popular sources?

Browse the databases below to access a variety of popular sources. If you don't see your publication of interest on this list, try searching the library website or contacting a librarian for assistance.

- Major U.S. Newspapers: Resource Guide Contains information about accessing the Chicago Tribune, Christian Science Monitor, the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, the Wall Street Journal, and more.

- National Geographic A complete archive of National Geographic magazine, along with a cross-searchable collection of National Geographic books, maps, images and videos.

- The New Yorker Digital Archive Digital access to The New Yorker magazine. Includes commentary, criticism, essays, fiction, satire, cartoons, and poetry.

- NPR (National Public Radio)

Trade Sources

Trade sources (also known as Trade Publications) share general news, trends, and opinions in a certain industry. They are not considered scholarly, because, although they are generally written by experts, they do not focus on advanced research and are not peer-reviewed. Trade publications:

- are published trade associations or vendors.

- are written by staff writers, professionals, journalists or vendors in the field for professionals in a specific trade or industry.

- use field-specific technical language.

- rarely include sources, may offer short reference lists.

- have ads geared for the specific industry.

Image: Trade Publication Advertising, Rapp Advertising, Inc.

Finding Trade Publications

- Many databases, including OneSearch@IU, allow you to filter by "Trade Publications"

Books/Book Chapters

Many academic books will be edited by an expert or a group of experts. Unlike a scholarly article, which usually focuses on the results of one research project, a book is likely to include an overview of research or issues related to its topic.

Conference Proceedings

Conference proceedings are compilations of papers, research, and information presented at conferences. Occasionally, proceedings are peer-reviewed. Proceedings are more commonly encountered (via databases and other searching) in science and engineering fields than in the arts and humanities.

- When searching OneSearch@IU, you can filter results by selecting "Conference Materials" under format. Many databases contain a conference proceedings/materials filter.

Government Documents

The Government Printing Office disseminates information issued by all three branches of the government to federal depository libraries (including IU Libraries). Additionally, government departments publish reports, data, statistics, white papers, consumer information, transcripts of hearings, and more. Some of the information published by government offices is technical and scientific.

- To learn more about and access these materials, check out the Government Information guide or contact our Government Information, Maps, and Microform Services department.

Theses & Dissertations

Theses and dissertations are the result of an individual student's research while in a graduate program. They are written under the guidance and review of an academic committee but are not considered "peer-reviewed" publications.

- When searching OneSearch@IU, you can filter results by selecting "Dissertations/Theses" under format.

- Explore the Finding Dissertations and Theses Guide to learn more.

- IUScholarWorks is a repository where anyone affiliated with IU can share their research openly so that it is available for anyone in the world to read. It’s important to remember that this includes graduate students! Graduate students can share papers, data, posters, and even their dissertation in IUScholarWorks.

Grey Literature

Grey literature refers to the wide body of reports, conference proceedings, preprint literature, working papers and drafts, personal communications, technical notes, theses & dissertations, and other ephemeral scientific and research materials published by business, governmental, or academic organizations. While not often utilized for student assignments, this literature can be helpful for engaging with new ideas, alternative perspectives, and emerging scholarship.

- Explore the Grey Literature section of IU's Systematic Reviews & Evidence Based Reviews Guide to learn more about these sources.

Adapted from: Understanding & Evaluating Sources, NM State University Library (2022).

Techniques for Evaluating Sources

Now that we've discussed peer review and other types of sources, let's look at ways to evaluate these sources. Below, we will discuss media timescales, popular & media sources, what to do with sources, and some tests you can perform to evaluate credibility.

Media Timescales

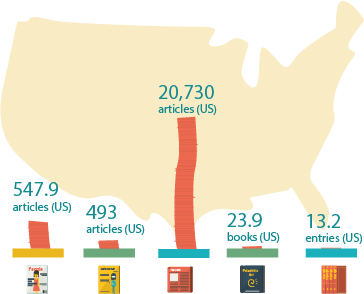

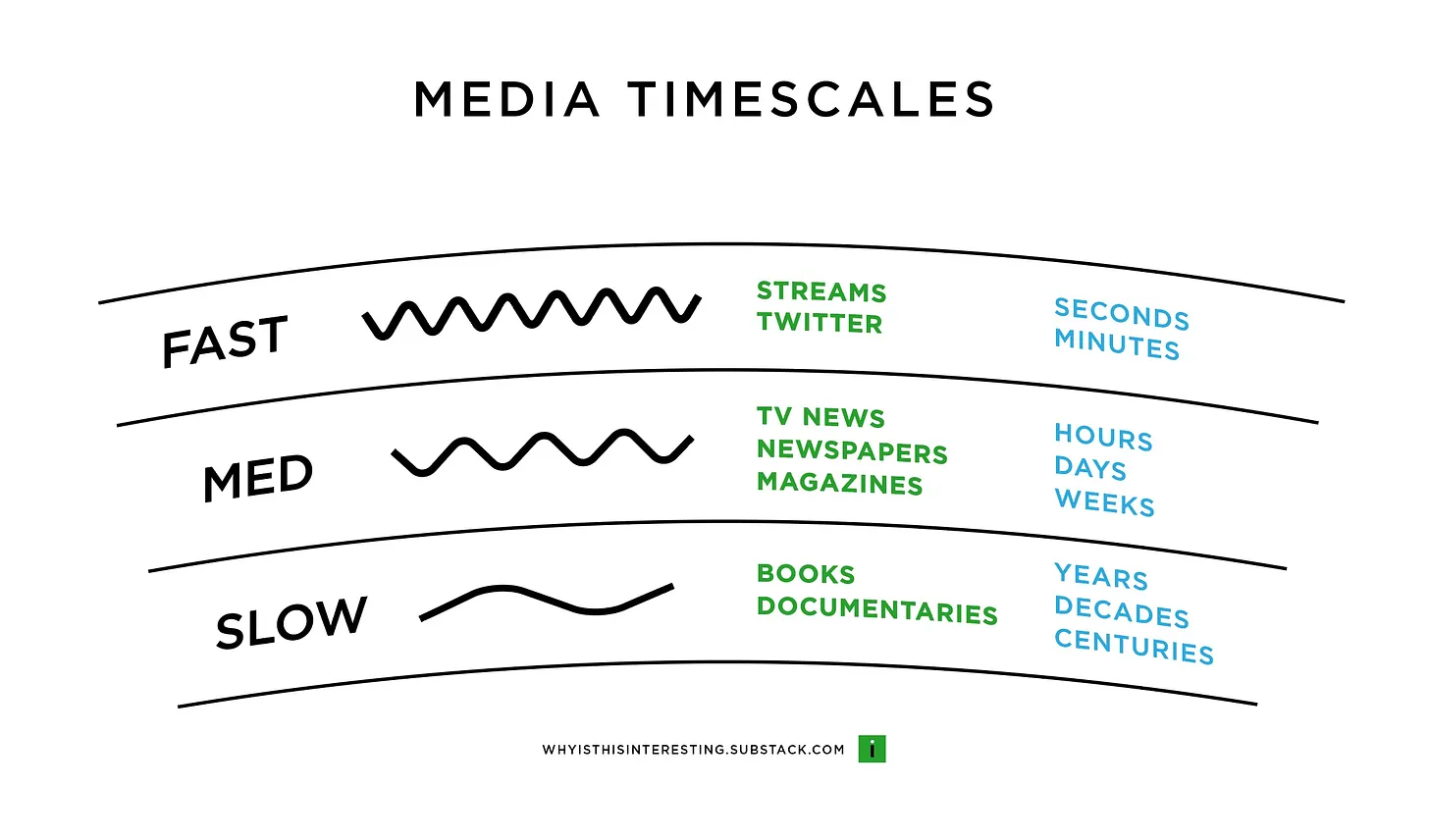

Peer-reviewed sources are only one type of source. Let's think about some ways to identify sources and whether or not they will be valuable for your research. Previously, we discussed the fact that sources go through various levels of review. The following graphic helps illustrate the speed at which media is published:

Image: The Media Timescale. Noah Brier, Why is this interesting? Substack (2022).

A source with a slow media timescale doesn't necessarily indicate this it is better or more useful than a source with a fast media timescale. Some research questions require a combination of all three timescales while others—say literature reviews or papers with peer-reviewed sources as a requirement—will require slower timescales. Thinking about which kind of sources you are looking for can help you determine if a source will bolster or detract from your paper.

Lateral Reading

Lateral reading is a technique, often used by professional fact-checkers, that evaluates a source's credibility through examining the external sources which refer to the original source. Lateral reading involves using Wikipedia, credible news sources, and other references to better understand a source's credibility, funding, reputation, conflicts, and biases. To perform lateral reading, open a new tab in your browser and search the name of your website of interest. You can also search for the author, publisher, and affiliated organization (i.e. funders, board members, supporters, etc.). Explore fact-checking websites such as PolitiFact, Snopes, and FactCheck.org and media bias charts such as Ad Fontes or Allsides. Using lateral reading can help you evaluate many different types of sources including social media, websites, blogs, and news outlets. For more information on lateral reading, see Salem State University's How-To Guide and the Lateral Reading infographic from University of Louisville Libraries below:

Image: Evaluating Online Resources Through Lateral Reading. University of Louisville Libraries (2022).

Video: Sort Fact from Fiction Online with Lateral Reading. Stanford History Education Group (2020).

Media and Popular Sources

Popular sources typically refer to general interest publications like newspapers and magazines. While different from scholarly sources, some newspapers and magazines might be useful in helping you answer your research question. For example, if you are performing research on public policy and information campaigns during the COVID-19 pandemic, the Twitter feed of a local health organization might offer valuable information. Magazine articles, newspapers, and blogs can inform you about the public perception of an event during a certain time and how people reacted to said event. Popular sources can also provide simplified descriptions of scholarly research, background information, or offer opinions and more personal points of view on a topic. See our section on News & Newspapers to learn more about evaluating popular sources.

Photograph: Newspaper stand. Ed Yourdon, Flickr (2008).

How can I use different sources?

Below is a method called BEAM, which asks you to consider the function of your source—what it is and how you might want to use it in your paper. For example, a passage from a novel might work better in a body paragraph of your essay rather than in the introduction or conclusion.

| Source Function | Explanation | Types of Sources | Where can I use it? |

|---|---|---|---|

| B: Background | Factual and noncontroversial information, providing context | Encyclopedia articles, overviews in books, statistics, historical facts | Introduction |

| E: Exhibit/ Evidence | Data, observations, objects, artifacts, documents that can be analyzed | Text of a novel, field observations, focus group transcriptions, questionnaire data, results of an experiment, interview data (primary sources) | Body/Results |

| A: Argument | Critical views from other scholars and commentators; part of the academic conversation | Scholarly articles, books, critical reviews (e.g. literacy criticism), editorials | Body, sometimes in Introduction or in Literature Review |

| M: Method | Reference to methods or theories used, usually explicit though may be implicit; approach or research methodology used | Part of books or articles with reference to theorists (e.g. Foucault, Derrida) or theory (e.g. feminism, post-colonialism, new historicism etc.); information on a research methodology | Methods or referenced in Introduction or Body |

Table: Source Functions: Background, Exhibits, Argument, Method (BEAM). UC Merced Library, (2022).

Evaluating Credibility

When locating and evaluating resources, you can use the SCAAN test to help determine if they are appropriate to use, reliable, and relevant:

- (S)ource type: Does this source answer your research question? Is it an appropriate type (scholarly or popular, for instance) for your question? Does this contain the information you need to support your argument?

- (C)urrency: Is this source up-to-date? Do I need a resource that contains historical information?

- (A)ccuracy: Is this source accurate? Does its logic make sense to me? Are there any internal contradictions? Does it link or refer to its sources? Does more current data affect the accuracy of the content?

- (A)uthority: Who created or authored this source? Could the author or creator bring any biases to the information presented? Is the author or creator a reputable or well-respected agent in the subject area?

- (N)eutrality: Is this source intended to educate, inform, or sell? What is the purpose of this source? Are you looking for a piece that is not neutral?

There are a number of other, similar "tests" that you can use to assess the credibility and utility of information and resources you find. These include:

- ACTUP: Author, Currency, Truth, Unbiased, Privilege

- CARBS: Currency, Authority, Relevancy, Biased or Factual, Scholarly or Popular

- CARS: Credibility, Accuracy, Reasonableness, Support

- DUPED: Dated, Unambiguous, Purpose, Expertise, Determine (source)

- IMVAIN: Independent, Multiple sources quoted, Verified with evidence, Authoritative, Informed, Named sources

- RADAR: Rationale, Authority, Date, Accuracy, Relevance

- CRAAP: Currency, Relevance (source), Accuracy, Authority, Purpose (neutrality):

There isn't one perfect way to evaluate a source, and every source has a potential use even if it isn't relevant for your particular research. The frameworks we've provided here are multiple ways to understand the value and use of the sources you'll find, but also consider your own perspective and embodied knowledge when engaging with sources to determine whether and how they should be used.

Whichever evaluation you use, remember that lived experience is a form of expertise and therefore, it is often helpful to consider the position and experiences from which an author writes as part of your source evaluation process. You may also want to reflect on your own biases when reviewing your information. How might your identity and positionality impact your consideration or evaluation of a source? If the source had the opposite position or result, how would that affect your opinion of its validity?

Video: Evaluating Sources. UOW Library (2018).

Citations

- Evaluating Information Sources (USC Libraries Research Guides)

- The Media Timescale Edition (Noah Brier. Why is this interesting? Substack 2022).

- Lateral Reading: A How-To (Salem State University)

- Lateral Reading (University of Louisville Libraries)

- Evaluating Sources Using Lateral Reading (The Ohio State University Teaching & Learning Resource Center Milton Academy)

- GEN: Source Evaluation: Lateral Reading (Milton Academy)

Further Reading

Developing Information Literacy Skills: A Guide to Finding, Evaluating, and Citing Sources by

ISBN: 9780472037667Publication Date: 2020-05-04Developing Information Literacy Skills provides guidance and practice in the skills needed to find and use valid and appropriate sources for a research project. Anyone who does academic research at any level can benefit from ways to improve their information literacy skills. The book focuses on providing students with the critical-thinking and problem-solving skills needed to: (1) identify the conversation that exists around a topic, (2) clarify their own perspective on that topic, and (3) efficiently and effectively read and evaluate what others have said that can inform their perspective and research. The critical-thinking and problem-solving skills practiced here are good preparation for what students will encounter in their academic and professional lives.The Research Virtuoso: How to Find Anything You Need to Know by

ISBN: 9781554513949Publication Date: 2012-02-01An essential tool for every student! Armed with this lively guidebook, students will be ready to face the often daunting prospect of conducting serious research in the information age. Fully revised, The Research Virtuoso covers all aspects of research: how to decide on a topic, take notes, skim material, evaluate which sources (especially those on the Internet) are most reliable, organize information, and create a bibliography. Readers will also learn how to access a treasure trove of sources they may never have known existed, such as special collections and private libraries.Falsehood and Fallacy: How to Think, Read, and Write in the Twenty-First Century by

ISBN: 9781487588632Publication Date: 2021-04-07Falsehood and Fallacy shows students how to evaluate what they read in a digital age now that old institutional gatekeepers, such as the media or institutions of higher education, no longer hold a monopoly on disseminating knowledge. Short chapters cover the problems that exist as a result of the current flow of unmediated information, Fake News, and bad arguments, and demonstrate how to critically evaluate sources—particularly those that appear online. Kilcrease discusses how to be on the lookout for bad arguments and logical fallacies and explains how students can produce clear and convincing academic writing.Student Guide to Research in the Digital Age: How to Locate and Evaluate Information Sources by

ISBN: 1591580994Publication Date: 2005-12-30One of the most perplexing aspects of research today is what to do when there's too much information on a topic. What then of the librarian, charged with teaching new generations to appreciate the search for intellectual wheat, especially when the chaff has greater appeal? The key, suggests Leslie Stebbins, is to impress upon students the importance of good filtering instincts and careful management of search results. At the same time, it is equally essential to impress upon them the particular challenges and controversies that accompany research in a digital environment. Chapter one provides a step-by-step introduction to both research and critical evaluation that can be followed for any assignment. Chapters two through seven focus on specific types of information resources: when to use them, where to find them, and how to evaluate them. Chapter eight offers guidance on how to develop a note-taking system, cite sources, avoid plagiarism, and organize references.