Introduction

You've read your assignment, crafted a research question, and assembled sources, now it's time to write! Beginning a paper can feel daunting and scary—that's okay! The tips below can help you work your way through the writing process (and remember that writing is just that: a process). Writing can be thought of as recursive, involving trial-and-error. Below we will discuss Academic Style Guides, inclusive writing practices, gender-inclusive writing, and resources to help you along on your writing journey.

Style Guides

What is an Academic Style Guide?

A style guide is essentially a set of writing rules for documents written in English. You can think of it as an instruction manual for your writing with guidelines for syntax, grammar, formatting, and citations.

Three of the most commonly used Academic Style Guides are:

- APA (American Psychological Association): Used by Education, Psychology, and Sciences

- MLA (Modern Language Association): Used by the Humanities

- Chicago: Used by Business, History, and the Fine Arts

If your are unsure about which style guide you should use, reach out to your professor. Often, the style guide will be listed in your assignment. For more information about these guides, visit our Citing Sources page.

Inclusive Writing

Style Guides for Inclusive Writing

Writers can contribute to a culture of equity by adopting inclusive writing practices. Inclusive language understands that language is not inherently neutral—many of the ways that we've been taught to write, speak, refer to, and think about people and events reflect societal biases. By using inclusive language, writers can show respect for individual differences and experiences. When thinking about how to address and write about people, especially ones who hold identities that are different from yours, it is helpful to find resources written by people of those communities on how they should be addressed. Engaging with the resources below can help your writing become more inclusive, ultimately allowing for it to be read by a larger and more diverse audience.

Many of the style guides listed below come from standards in the field of journalism. These guides discuss word choice and how language is changing with time. We have also created our own section about gender-inclusive language in the next box.

- Digital Journalism Style Guide of Inclusive Language (Language, Please)

- Conscious Language Guide (Conscious Style Guide). Features individual style guides for various communities and groups.

- Inclusive Language Resources (University of British Columbia)

- Glossary of Immigration Terms (Freedom for Immigrants)

- Guide to Covering Asian Pacific America (Asian American Journalists Association (AAJA)). Currently under revision.

- National Association of Black Journalists Style Guide (National Association of Black Journalists (NABJ))

- Cultural Competence Handbook (March 2021) (National Association of Hispanic Journalists (NAHJ))

- Reporting on Indigenous Terminology (Native American Journalists Association (NAJA))

- Indigenous Media Reporting Guides (Native American Journalists Association (NAJA))

- Media Reference Guide (Gay & Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation (GLAAD))

- Socioeconomic Status Language Guide (APA Style)

Disability Style Guides:

- Disability Language Style Guide (National Center on Disability and Journalism)

- How To Write About People with Disabilities, 9th edition (The University of Kansas)

- Glossary of Ableist Terms & Alternatives (Autistic Hoya)

Inclusive Language Guides for Different Groups and Identities

The Guidelines on Inclusive Language and Images in Scholarly Communication by the Coalition for Diversity & Inclusion in Scholarly Communications (C4DISC) contains guides pertaining to:

- Age Try using age-inclusive writing in you assignments.

- Crime and Incarceration Consider how you discuss people who are incarcerated and those affected by the criminal justice system.

- Family and Relationship Status Many words related to families and relationships are gendered. Terms like guardian and caregiver avoid stereotypes about who is expected to perform childcare.

- Gender, Gender Identity, and Sexual Orientation Give people the agency to determine the language used to describe them.

- Geopolitics Consider point of view, relevancy, and terminology when discussing geopolitical issues.

- Health Consider how you discuss a person's appearance, weight, and other physical attributes. Is it necessary to mention these characteristics?

- Immigration The language used to describe people’s immigration or citizenship status can reinforce stereotypes.

- Race and Ethnicity Use the terms preferred by the communities you are writing about.

- Religion, Atheism, Spirituality Consider context and perspective, many religious groups experience discrimination depending on local demographics.

Linguistic Justice

In the Linguistic Justice view of learning, multiple expressions of diversity (e.g., race, social class, gender, language, etc.) are not only recognized but also regarded as assets. Linguistic justice believes that culture and language are not simply additions to but, rather, critical components of education. It raises awareness of the ways hierarchies of oppression, particular in language, limit and individual's and/or group's access to their full potential. In education, the unwillingness to accept multiple Englishes has led to an education system which serves those who speak and write in "Standard American English" at the expense of students who utilize other vernaculars as well as students of multiple literacies.

For more information, see the videos and books listed below:

Video: Linguistic Justice: Black Language, Literacy, Identity, and Pedagogy. Film by Peter Johnston featuring Dr. April Baker-Bell (2020).

Linguistic Justice: Black Language, Literacy, Identity, and Pedagogy by

ISBN: 9781315147383Publication Date: 2020-04-28Bringing together theory, research, and practice to dismantle Anti-Black Linguistic Racism and white linguistic supremacy, this book provides ethnographic snapshots of how Black students navigate and negotiate their linguistic and racial identities across multiple contexts. By highlighting the counterstories of Black students, Baker-Bell demonstrates how traditional approaches to language education do not account for the emotional harm, internalized linguistic racism, or consequences these approaches have on Black students' sense of self and identity. This book presents Anti-Black Linguistic Racism as a framework that explicitly names and richly captures the linguistic violence, persecution, dehumanization, and marginalization Black Language-speakers endure when using their language in schools and in everyday life. A crucial resource for educators, researchers, professors, and graduate students in language and literacy education, writing studies, sociology of education, sociolinguistics, and critical pedagogy, this book features a range of multimodal examples and practices.

Video: Why English Class is Silencing Students of Color. Jamila Lyiscott, TEDxTheBenjaminSchool (2018).

Black Appetite. White Food by

ISBN: 9781351062381Publication Date: 2019-05-03Black Appetite. White Food. invites educators to explore the nuanced manifestations of white privilege as it exists within and beyond the classroom. Renowned speaker and author Jamila Lyiscott provides ideas and tools that teachers, school leaders, and professors can use for awareness, inspiration, and action around racial injustice and inequity. Part I of the book helps you ask the hard questions, such as whether your pedagogy is more aligned with colonialism than you realize and whether you are really giving students of color a voice. Part II offers a variety of helpful strategies for analysis and reflection. Each chapter includes personal stories, frank discussions of the barriers you may face, and practical ideas that will guide you as you work to confront privilege in your classroom, campus, and beyond.

Habits of White Language (HOWL)

"To really understand what White language supremacy is exactly, and how we might decenter and counter it in our classrooms, we have to understand what the habits of White language, or HOWL, are. Their use and circulation is an important aspect of White language supremacy."

—Dr. Asao B. Inoue

Dr. Asao B. Inoue is a professor of Rhetoric and Composition in the College of Integrative Sciences and Arts at Arizona State University. In 2021, Dr. Inoue coined the term HOWL, which stands for Habits of White Language. All groups of people have linguistic habits which can indicate anything from that group's values to its way of seeing others. Dr. Inoue argues that though habits are natural in language, issues arises when "one group’s habits get used as the standard by which all other people are judged, regardless of their own habits or their goals as students or people." Dr. Inoue identifies six habits of white language:

- Unseen, Naturalized Orientation to the World: This orientation "assumes, or takes as universal, its own proximities or capabilities to act and do things that are inherited through one’s shared space." For example, a teacher may embody this habit when they assume that their students have "access to the things, language, concepts, histories, and logics that they do," such as their vernacular habits, historical knowledge, or a certain cultural background.

- Hyperindividualism: This stance values the individual over the collective. "In this way," states Dr. Inoue, "the point of society, school, the classroom and its activities is to serve the interests and growth of the individual, not the community."

- Stance of Neutrality, Objectivity, and Apoliticality: This orientation assumes that a speaker is neutral, apolitical, non-racial, and non-gendered. This stance may manifest in a classroom when a rubric or set of language expectations is "assumed to be apolitical, outside of the gendered and racialized people who made it or use it."

- Individualized, Rational, Controlled Self: In this stance, a person is conceived of as "an individual who is primarily rational, self-conscious, self-controlled, and self-determined." This orientation means that success and failure are individual in nature and are a result not of systems but of the singular person operating within them. In other words, an individual is seen as failing to succeed in a system rather than a system failing to serve an individual.

- Rule-Governed, Contractual Relationships: This habit focuses on an individual's contractual relationships with others, whether through a classroom syllabus or the laws of a society. "There is an importance attached to laws, rules, fairness as sameness and consistency, so fair classrooms are understood to be ones that treat every individual exactly the same regardless of who they are, how they got there, where they came from, or what their individual circumstances are for learning."

- Clarity, Order, and Control: This habit "focuses on reason, order, and control as guiding principles for understanding and judgement." 'Objectivity' is valued over over the subjective and emotional. "Rigor, order, clarity, and consistency are all valued highly and tightly prescribed, often using a dominant standardized English language that comes from a White, middle- to upper-class group of people."

Habits of white language contribute to white language supremacy which operates not only in educational contexts but in social, professional, and personal spaces. HOWL, though it values the individual over all else, does not actually appreciate an individual's differences, rather, it encourages conformity which rejecting a person's creative and emotional sides. If you are an educator, teacher, or anyone in a position of power, think about how HOWL is reinforced by your student assessments, feedback, employee evaluations, and everyday communication. If you are a student, consider how HOWL manifests in your everyday communication and reception of your peers' work. Though institutions will often reinforce habits of white language, and going against these habits may have repercussions, thinking about how these habits manifest in your personal life is a great place to start.

For more information, read Dr. Inoue's "Blogbook—The Habits of White Language (HOWL)" and follow his blog.

Video: Dr. Asao B. Inoue, #4C19 Chair's Address. National Council of Teachers of English (2019).

Citations: Asao B. Inoue, The Habits of White Language (HOWL) (July 3, 2021).

Sources

- Radical Copy Editor (Alex Kapitan)

- Inclusive Writing Guide (University of Idaho, Brand Resource Center)

- For More Inclusive Writing, Look to How Writing Is Taught (Laila Lalami, The New York Times, 2021)

Further Reading

- Inclusive and Antiracist Writing Overview (Simon Fraser University)

- Inclusive Writing Guide (English) (McGill University)

- Inclusive Assessment of Student Learning (Brown University)

Academic Style & Gender-Inclusive Writing

Illustration: Kaz Fantone, NPR (2021).

Academic style guides agree: honoring and using a person’s correct personal pronoun is a matter of respect, and it's good style.

All three major Academic Style Guides (APA, the Chicago Manual of Style, and MLA) agree that a person’s correct personal pronouns (they, he, she, etc.) should be respected and used at all times in formal and academic writing. To determine the pronouns of someone you are writing about, refer to their biography, check social media accounts, personal websites, faculty/student profiles, or if possible, ask them what pronouns they use. Remember that it is not possible to infer a person’s pronouns just by looking at them and that some people use multiple sets of pronouns. If a person's pronouns are unknown or cannot be determined, using the singular “they” may be a solution—if you are writing in APA or MLA. For those using Chicago, the guide recommends rewriting the text in a way that does not require using personal pronouns (Chicago). Always take care to use correct personal pronouns.

Try this Gender Pronouns Worksheet from UMBC for practice using pronouns.

Illustration: Pronouns, Valerie Morgan (2021).

What are personal pronouns?

A pronoun is a word that refers to a person, group, or thing.

Everyone has pronouns and getting these pronouns right is not exclusively a transgender and/or non-binary issue. Historically, English offered only three personal pronouns: masculine (he), feminine (she), and the un-gendered “it." The lack of a widely-used gender neutral pronoun in English has long been criticized, since, in many instances, people default to using “he/him” when referring to a generic individual in the third person. Not only does the use of gendered he/she pronouns reinforce a socially constructed gender binary, it also contributes to the use of the masculine "he" as our default.

Since the three personal pronouns, he/she/it, do not adequately express the variety of gender expressions that have been present throughout history, some people choose to go by pronouns that more accurately reflect their gender. Sometimes, this pronoun is a gender neutral pronoun such as "they." "They" is already commonly used as a singular pronoun when talking about someone with unknown pronouns. For example, we might say, "someone left their jacket on this chair" or "they just went outside."

Using someone's preferred pronouns is not only respectful, it shows that you care and are working to create a welcoming environment for them and others. Below is a chart that lists some of the most commonly used personal pronouns along with examples of their use.

| Pronoun |

Nominative (subject) |

Objective (object) |

Possessive Determiner |

Possessive Pronoun |

Reflexive |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| He | He laughed | I called him | His dog barks | That is his | He likes himself |

| She | She laughed | I called her | Her dog barks | That is hers | She likes herself |

| They | They laughed | I called them | Their dog barks | That is theirs | They like themself |

| Fae | Fae laughed | I called faer | Faer dog barks | That is faers | Fae likes faerself |

| Per | Per laughed | I called per | Per dog barks | That is pers | Per likes perself |

|

Ze and hir (zee/hear) |

Ze laughed | I called hir | Hir dog barks | That is hirs | Ze likes hirself |

This pronoun chart is directly based off the one created by the University of Wisconsin Madison's Gender and Sexuality Campus Center.

Adapted from: Laurel Wamsley, A Guide To Gender Identity Terms, NPR (June 2, 2021); Sala Levin, How to Use Pronouns Appropriately, MarylandToday (June 28, 2021).

What is gender-inclusive writing?

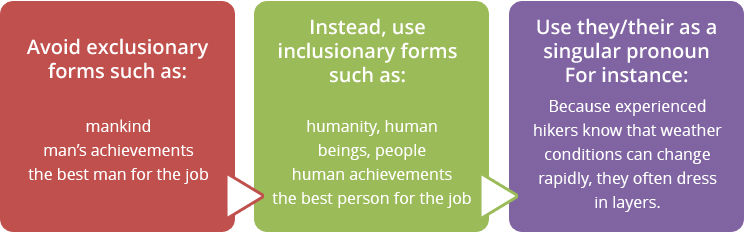

Academic style guides agree on the importance of achieving gender-neutral writing, and the problem of using “he” as a universal pronoun. You have probably encountered texts where masculine nouns and pronouns have been used to refer to a subject with unknown pronouns or to a group of people that does not only include men. For example, terms and phrases such as "freshman" and "all men are created equal" were coined when only men could access higher education and political life. We know, however, that much has changed in the English language since then. Most readers no longer understand the word “man” to be synonymous with “person,” so clear communication requires writers to be more precise.

For a time, academic style guides suggested the use of “he or she” or alternating between “he” or “she” in writing. You may have seen manifest as the use of "he/she" or "s(he)." These constructions are now acknowledged as being not only clunky and awkward, but exclusionary to people who do not fit neatly into the gender binary implied by “he or she.”

Using gender-neutral language has become standard practice in both journalistic and academic writing, as you’ll see if you consult the style manuals for different academic disciplines. Gender-neutral language avoids bias toward certain genders. In other words, it avoids the use of masculine or feminine pronouns and prioritizes gender-inclusive nouns and pronouns. The singular “they,” in use since the 14th century in informal and spoken speech, is a gender-inclusive pronoun that can be used in academic writing. More on the history of singular “they” can be found at the Oxford English Dictionary’s website and Historians.org.

How can I make my writing gender-inclusive?

"Men" and words that end in a form of "-man" are prominent in the English language. See below for a chart on ways that you can replace these gendered nouns with ones that are more inclusive.

| Gendered Noun | Gender-Neutral Options |

|---|---|

| man | person, individual, one |

| mankind | humanity, human beings, people |

| freshman | first-year, first-year student |

| man-made | machine-made, synthetic, artificial, inorganic |

| the common man | the average person, laypeople |

| chairman | chair, chairperson, head, coordinator |

| mailman | mail carrier, postal worker, letter carrier |

| actor, actress | actor |

| Sir (in “Dear Sir,” etc.) | Dear Editor, To Whom it May Concern, etc. |

Image: Inclusionary word choices chart, Enago Academy.

Gender-Inclusive Language Checklist

Ask the following questions as you write and review your paper:

- Have you used “man” or “men” or words containing them to refer to people who may not be men?

- Have you used “he,” “him,” “his,” or “himself” to refer to people who may not be men?

- If you have mentioned someone’s sex or gender, was it necessary to do so?

- Example: Did you use a phrase like "female doctor" or "male secretary"? Use the unmodified "doctor" and "secretary" if possible.

- Do you use any occupational (or other) stereotypes?

- Do you provide the same kinds of information and descriptions when writing about people of different genders?

- Imagine a diverse group of people reading your paper: Would each reader feel respected? Would they feel like they are represented in your writing?

Adapted from: The Writing Center, UNC Chapel Hill, Gender-Inclusive Language.

The Singular "They" in 2023

Academic Style Guides adapt slowly to changes in grammar and these guides are always in flux. To understand Academic Style Guides’ current and past positions on singular “they” as a gender-neutral unknown referent, it is important to keep in mind that Academic Style Guides do not create grammatical rules. Rather, they establish formal guidelines that follow spoken and grammatical conventions. Academic Style Guides can be slow to adopt conventions they might see as temporary. Despite the long history of the singular “they,” which mirrors the grammatical evolution of singular “you,” some style guides have waffled on sanctioning its use.

As of 2023, all three major guides (APA, MLA, and Chicago) acknowledge the ubiquity of singular “they” for use with an unknown referent in informal writing and speech. However, only one of the three guides, the 7th Edition of APA’s Style Guide, fully endorses the use of singular “they” as “a generic third-person singular pronoun to refer to a person whose gender is unknown or irrelevant to the context of usage” (APA, 120). MLA, which leaves grammar largely up to the discretion of the author, neither endorses nor prohibits the use of singular “they” in this sense. As a result, it is acceptable in MLA Style. The Chicago Manual of Style (CMOS) has a particularly complicated history with singular “they” as a gender-neutral unknown referent. In the 1993 edition, it endorsed “they/their” in this sense (Chicago, 13th Ed. 2.98). However, this was removed from subsequent editions. Though CMOS acknowledges the ubiquity of this usage, it continues to prohibit its use and instead recommends rewriting the sentence in some way that eliminates the need for a pronoun. For more on the history of singular “they” and the Chicago Manual of Style, take a look at this 2018 article written by Cai Fischietto on IU Libraries’ website.

Further Reading on Gender-Inclusive Writing

- Suggested Rules for Non-Transsexuals Writing about Transsexuals, Transsexuality, Transsexualism, or Trans ____. (Jacob Hale)

- Style Guide (Trans Journalists Association)

- Gender Inclusive Language Handout (Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill)

Further Reading on the Singular Pronoun "They"

- The Evolution of the Singular "They" (Words at Play Blog, Merriam-Webster)

- Word of the Decade: Singular "They" (American Dialect Society)

- Academic Style Guides on the Singular Pronoun "They" (Cai Fischietto, IU Libraries Blog)

- Gendered Pronouns and Singular "They" (OWL at Purdue Writing Lab)

Further Reading—General

- A Guide on How Gender-Neutral Language Is Developing Around the World (Miriam Berger, The Washington Post)

- Gender-Inclusive / Non-Sexist Language Guidelines and Resources (University of Pittsburgh)

Writing Tutorial Services

Writing Tutorial Services (WTS) offers students one-on-one help with any phase of the writing process—from brainstorming to revising the final draft. When you visit WTS, you'll find a tutor who is a sympathetic and helpful reader of your prose.

WTS tutors can benefit IU Bloomington students with any writing background on any type of academic writing. WTS can help undergraduate and graduate students to:

- Develop strong thesis statements

- Develop effective outlines

- Find and integrate credible sources

- Identify patterns of error and fix these problems on your own

- Understand and avoid plagiarism

- Write effective answers to essay exam questions

WTS has a number of online style guides available, to help you with most of the classroom writing assignments you'll be expected to complete as a student.