Develop a Research Question

When starting out on your research, it is important to choose a research topic that is not only of interest to you, but can also be covered effectively in the space that you have available. You may not know right away what your research question is - that's okay! Start out with a broad topic, then conduct some background research to explore possibilities and narrow your topic to something more manageable.

Choose an interesting general topic. If you’re interested in your topic, others probably will be too! And your research will be a lot more fun. Once you have a general topic of interest, you can begin to explore more focused areas within that broad topic.

Gather background information. Do a few quick searches in OneSearch@IU or in other relevant sources. See what other researchers have already written to help narrow your focus.

- What subtopics relate to the broader topic?

- What questions do these sources raise?

- What piques your interest? What might you like to say about the topic?

Consider your audience. Who would be interested in this issue? For whom are you writing?

Materials obtained from Scott Libson, which were adapted from: George Mason University Writing Center. (2008). How to write a research question. Retrieved from http://writingcenter.gmu.edu/writing-resources/wc-quick-guides

Once you have done some background research and narrowed down your topic, you can begin to turn that topic into a research question that you will attempt to answer in the course of your research.

Keep in mind that your question may change as you gather more information and as you write. However, having some sense of your direction can help you evaluate sources and identify relevant information throughout your research process.

Explore questions.

- Ask open-ended “how” and “why” questions about your general topic.

- Consider the “so what?” of your topic. Why does this topic matter to you? Why should it matter to others?

Evaluate your research question. Use the following to determine if any of the questions you generated would be appropriate and workable for your assignment.

- Is your question clear? Do you have a specific aspect of your general topic that you are going to explore further?

- Is your question focused? Will you be able to cover the topic adequately in the space available?

- Is your question sufficiently complex? (cannot be answered with a simple yes/no response, requires research and analysis)

Hypothesize. Once you have developed your research question, consider how you will attempt to answer or address it.

- If you are making an argument, what will you say?

- Why does your argument matter?

- What kinds of sources will you need in order to support your argument?

- How might others challenge your argument?

Adapted from: George Mason University Writing Center. (2008). How to write a research question. Retrieved from http://writingcenter.gmu.edu/writing-resources/wc-quick-guides

A good research question is clear, focused, and has an appropriate level of complexity. Developing a strong question is a process, so you will likely refine your question as you continue to research and to develop your ideas.

Clarity

Unclear: Why are social networking sites harmful?

Clear: How are online users experiencing or addressing privacy issues on such social networking sites as Instagram and Facebook?

Focused

Unfocused: What is the effect on the environment from global warming?

Focused: How is glacial melting affecting penguins in Antarctica?

Simple vs Complex

Too simple: How are doctors addressing diabetes in the U.S.?

Appropriately Complex: What are common traits of those suffering from diabetes in America, and how can these commonalities be used to aid the medical community in prevention of the disease?

Adapted from: George Mason University Writing Center. (2008). How to write a research question. Retrieved from http://writingcenter.gmu.edu/writing-resources/wc-quick-guides

Scholarly vs. Popular Sources

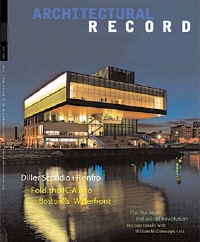

|

Criteria |

Scholarly Journal |

Trade Publication |

Popular Magazine |

|

Examples |

|||

|

Accountability |

Articles usually peer-reviewed before publication by other scholars or experts in the field) |

Articles evaluated by editorial staff who may be experts in the field, not peer-reviewed Often published by commercial enterprises, though may come from specific professional organizations |

Articles evaluated by editorial staff, not experts in the field. Edited for format and style. |

|

Audience |

Scholarly researchers, faculty and students |

Professionals in the field |

The general public |

|

Author |

Articles are written by experts in the field. Include author credentials. Author affiliations listed, usually at bottom of the first page or at end of article. |

Articles may be written by a member of the editorial staff, a scholar or a free lance writer. Author is usually a professional in the field, sometimes a journalist with subject expertise. |

Article may be written by a member of the editorial staff or a free lance writer. Author is frequently a journalist paid to write articles; may or may not have subject expertise. |

|

Content |

Articles contain an abstract (descriptive summary of the article contents) before the main text of the article. Often report original research and reviews while expanding on existing theories. Offer critiques on previously published materials. |

Report current news, trends and products in a specific industry. Include practical information for professionals in the field or industry. Cover news about people, organizations, new publications, conferences, and topical issues. |

Articles are typically a secondary discussion of someone else's research; may include personal narrative or opinion. Cover news, current events, hobbies or special interests. |

|

Graphics |

Illustrations are few and support the text, typically in the form of charts, graphs and maps. Few or no advertisements. |

Photographs, graphics and charts. Trade-related advertisements targeted to professionals in the field. |

Slick and attractive in appearance with color graphics. Glossy advertisements and photographs. |

|

Language |

Specialized terminology or jargon of the field. Assume that the reader is familiar with the subject. |

Specialized terminology or jargon of the field, but not as technical as a scholarly journal. Geared to any educated audience with interest in the field. |

Short articles are written in simple language.. Language for any educated audience, does not assume familiarity with the subject matter. |

|

Layout & Organization |

Very structured. Includes article abstract and bibliography. May include sections on methodology, results (evidence), discussion, conclusion, and bibliography. Page numbers consecutive throughout the volume.(Example: Issue 1 will end on page 455; Issue 2 will begin on page 456.) |

Informal. Articles organized like a journal or a newsletter. Typically use glossy paper. |

Very informal. May include non-standard formatting. May not present supporting evidence or a conclusion. |

|

References |

Verifiable quotes and facts. Sources cited in footnotes or bibliographies. Bibliographies generally lengthy, cite other scholarly writings. |

Occasionally include brief bibliographies. Not required to report any research results. |

Sources sometimes cited, but not usually in footnotes or a bibliography Information is often second- or third-hand, original source rarely mentioned. |

|

Examples |